21.08.2015 | Blog | BY: Clementine De Pressigny

The trio shot beautiful imagery for the latest Lonely campaign, and we got to ask them a few questions about it.

How did you chose who to shoot?

Petra Collins: We shot ourselves, each other and our friends. It was a liberating experience to be shot and shoot each other in lingerie, because our imperfections were on full display, which was awesome.

Was there a particular concept behind the shoot?

Petra: I guess we just wanted to make it super intimate, to explore our relationships to our own bodies, to each others bodies and to the environment.

You guys are all friends, how do you think that changes the dynamic of a shoot?

Petra: It’s the only way I shoot. I like to surround myself with my friends and peers and I think that’s what always gets the best results.

What did you shoot on?

Petra: A Yashica FX-3000

Is lingerie important to you?

Mayan Toledano: I have more underwear than any other item of clothing—I own maybe 200 pairs. Sometimes I’ll embroider them, sometimes I’ll print or draw on them and some have faded period stains that never washed off. They’re like a diary, I keep memories through them. I still own a pair of purple undies that I had on the night I first stayed with my first boyfriend. Lingerie is the closest thing to our bodies and that’s what makes it so personal.

Tell us about the girls you shot, why are they special to you?

Mayan: We picked girls who we met along the way and who inspire us. We shot an actress, an artist, a designer and a journalist—each one was different and special in her own way. It was cool to meet new people and hear their personal stories, and since we shot in their homes the feeling was super intimate right away. We got to see what the girls are really like, what they do, what they feel comfortable wearing and how they look at themselves in the mirror. When we wear lingerie at home we wear it primarily for ourselves, so it felt really special when the girls invited us into that world.

You didn’t shoot models. Why is it important to you to feature different female bodies?

Mayan: Representation is so important to all of us, and seeing diversity of body types is so rare, especially in lingerie imagery. Lonely gave us the freedom to cast girls and shoot each other without having to worry about the extreme beauty standards out there. Beauty is everywhere, but it is definitely not just what’s being fed to us by the media. We’re all beautiful with our stretchmarks, freckles, cellulite and all the other bits we are taught to hate about ourselves. The only reason we see these as flaws is because we somehow believe the images we see every day, the ones that show models who have been Photoshopped to such a degree that nothing is real anymore. When we start loving ourselves with our “flaws”, we can stop judging others for having them. I think self love is the first step in acceptance and support. It’s something we dealt with a lot on this project because we were both modeling and shooting. We all have our bad days where we feel more self-conscious, but the greatest thing about working with Zara and Petra is that we’re all so close, we feel comfortable and relaxed with each other, there’s no judgment whatsoever. They are both so beautiful to me because I value who they are.

What is the dynamic like when you’re working with your best friends?

Mayan: We get really hyper. We each get excited over different things and follow each other’s instincts, which is amazing. I feel so safe and creative with my best friends, the whole shoot never once felt like work. It was just us doing what we do—chilling, taking photos, laughing and screaming at each other.

Lonely is a brand that supports a healthy, natural body image, how did you aim to communicate that, aside from not using models?

Mayan: When we take photos of other girls or each other we approach it in a way that is super soft and stress free. The atmosphere on set is very similar to the photos; it’s personal and close and I think the photos communicate that feeling. I’d rather see a girl feeling comfortable and loving herself, wearing what she herself picked, rather than dictating how everything is going to look. The Lonely Girls Project is so important because it features different genders, ethnicities and body types. It is personal and real and I think more women can relate to it. We still have a long way to go before we all feel represented, but Lonely is one of the only brands currently taking a leap towards change.

Where do you shop for lingerie?

Mayan: My mom still buys underwear for me. I never go into lingerie stores because I personally don’t feel like they’re designed for me. From campaign to product it’s made to appeal to men more than it is about female empowerment. but the products are only for women—it’s kinda crazy. If I wear a bra I prefer ones from Lonely because they aren’t padded. What are padded bras about? We all have different shapes and sizes and those to me are like wearing a shield.

What was the idea behind the Lonely campaign?

Zara Mirkin: In my mind it was an extension of the Lonely Girls Project we started a few years ago. It was about initiating a change from lingerie imagery being made for the male gaze, to finally being for females—with real woman wearing underwear in their natural habitats—showing all their so-called imperfections.

Tell us about your personal relationship to lingerie.

Zara: I never thought about it much until I started working for Lonely five years ago. Until then I only ever wore basic cotton underwear that I’d hold onto for years—no matter how stained or ripped they got, or how weird the memories they conjured. I remember when I was 18 my boyfriend made a pattern from a pair of knickers I had left at his house, he made me cotton undies that he wrote his name on with a pen after watching The Virgin Suicides and seeing the character Lux Lisbon write Trip’s name on hers.

Starting the Lonely Girls Project changed how I looked at lingerie, because it gave me the experience of learning about the women I was shooting and their relationships with their bodies. Lingerie can be really powerful. It can tell stories and can reflect, or alter, what mood you’re in.

Tell us about the girls in the shoot…

Zara: They are all clever, kind, strong, hard working, beautiful and humble. It is always so important to me that I can have an interesting conversation and walk away having been inspired when shooting someone. Because we have the power to decide who we shoot I feel like the responsibility is on us to feature those who other woman can relate to and be inspired by. I know what we are doing is small in comparison to all the photos out there of fake, Photoshopped, unrealistic female bodies, but we can still make a difference.

What is like working with Mayan and Petra:

I feel so lucky and grateful that I get to work with my best friends all the time, mostly because it never feels like work. We do our best work together, because we push and inspire each other, while having so much fun and making each other laugh—or maybe laughing at each other…

Why has Lonely made such an impact?

I think a huge part of Lonely’s success has come from the Lonely Girls Project. Finally a lingerie label was photographing woman of all ages, sizes, ethnicities and careers, and from different parts of the world. With no make up and no Photoshop . Women want to look at woman they can relate to, those who look like them. These images were shot by women, for women—showing stretchmarks, hair, cellulite dimples and veins.

How do you chose lingerie?

Most of my underwear is still the same old, faded, stretched and stained cotton pieces… but now I own tons of Lonely because they make stuff that is beautiful and feels nice to wear.

zaramirkin.com

mayantoledano.com

petracollins.com

27.07.2015 | Art , Culture , Fashion | BY: Clementine De Pressigny

What started as two design students connecting over their love of everything girly, and their dislike of the elitism and limits imposed by fashion school, led to the creation of Me and You—a fashion label with a cult following. Mayan Toledano and Julia Baylis are the best friends behind the label known for its beautifully simple underwear emblazoned with ‘feminist’ in pastel pink lettering, floaty tulle dresses, and fitted T-shirts covered in lipstick kisses.

Me and You began while Baylis and Toledano were studying at Parsons School of Design in New York. “We started collaborating on art pieces because we really liked the print studio at our school and it was a good getaway for us from regular class—because we hated it,” says Toledano. “It was very business oriented,” adds Baylis. “It was either become an assistant designer or become the next big thing, but we really wanted to design stuff that is accessible.”

“We always say that Me and You is about going to that place when you’re a young girl and you’re sitting in your room, where you feel safe and comfortable and creative.”

Snatching time between classes and assignments, their collaboration continued to develop. But it was the response they received on social media that really pushed the best friends to take it from escapist pastime to an actual business. “We didn’t sit down and decide to start a clothing label together, it was very organic,” says Baylis. “We began to print pieces and then our friend Petra [Collins] photographed some of our stuff, we put some of it on Instagram and people were commenting on our work and getting excited about it.”

The internet has been a critical space for the fourth wave of feminism, and Me and You has found a dedicated fanbase among young females who aren’t afraid to call themselves part of the movement. While some brands have tried to use feminism in cynical, attention-seeking ways at a time when it’s getting renewed interest, for Toledano and Baylis it is instinctive. “The idea of feminism was always so natural to me, I don’t even remember first becoming aware of the word,” says Baylis. “The perception of the word has changed so much, it has and morphed through each wave of feminism.” This is what lead the duo to incorporate the word ‘feminist’ into their designs in the way that they have. “We decided to take that word, which is so loaded, and use it in a fun, accessible way, in a pretty way, making it something that girls can relate to,” says Toledano.

Those tired of homogenous fashion imagery so far from a representation of themselves are turning to a new era of creatives unafraid to offer up a different vision—like Baylis, Toledano and their collaborators, who include Barbara Ferreira, Petra Collins, Arvida Byström. The imagery created for Me and You, which is as much a part of the brand as the clothing, stands out for the diversity of girls—and occasional boy—featured. “Who we photograph is never calculated, it’s just people we see in real life or on Instagram,” says Toledano, “We would never airbrush our images, we show cellulite and whatever.” They have no qualms about body hair either, but point out that they see shaving as just as valid—what’s important is knowing that it’s a choice.

‘The idea of feminism was always so natural to me, I don’t even remember first becoming aware of the word.”

With Me and You, Baylis and Toledano have created a world of comfort, vulnerability and the freedom that comes with having total support from a community of like-minded individuals. That is perfectly encompassed by how they describe their label: “We always say that Me and You is about going to that place when you’re a young girl and you’re sitting in your room, where you feel safe and comfortable and creative. We always reference that place because we think that exists within everyone. It’s that place where you feel uninhibited, you feel yourself.”

www.itsmeandyou.com

Photography by Zara Mirkin

03.06.2015 | Art , Blog , Fashion | BY: Clementine De Pressigny

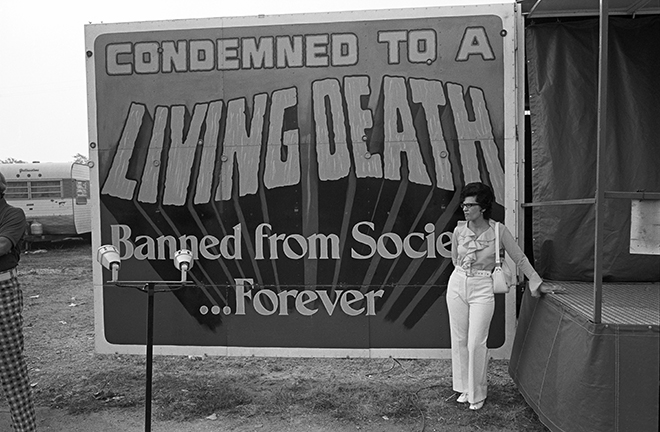

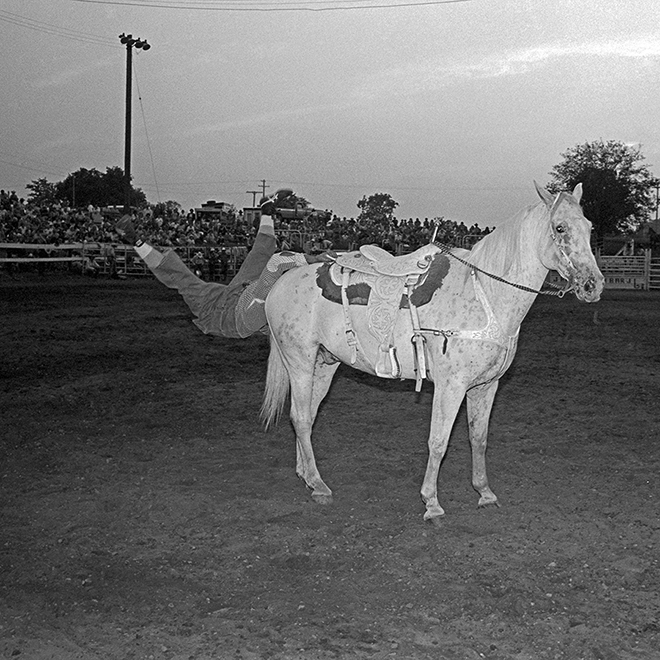

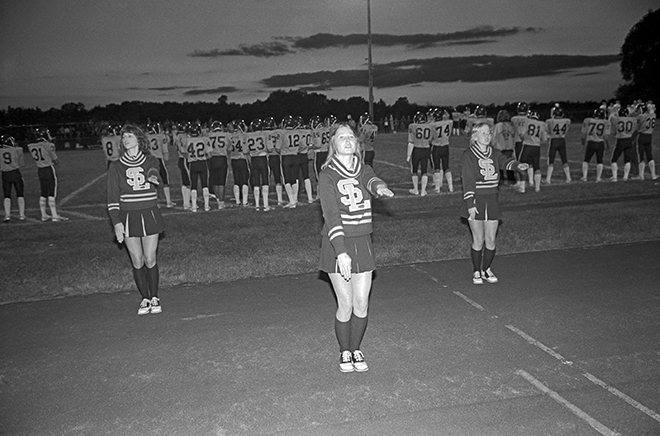

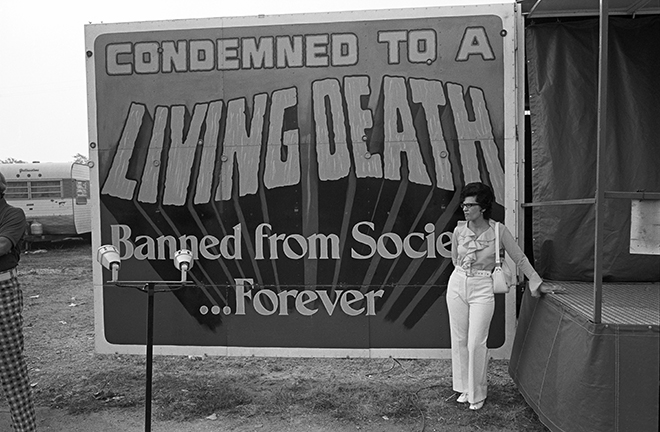

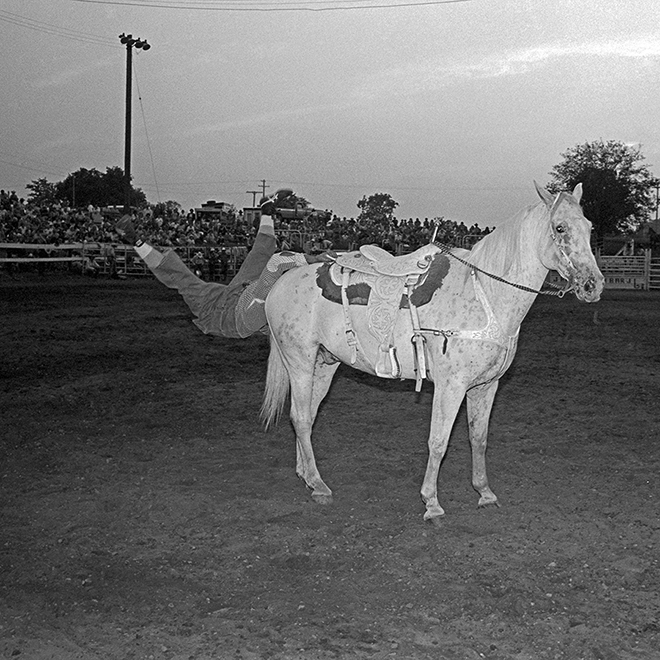

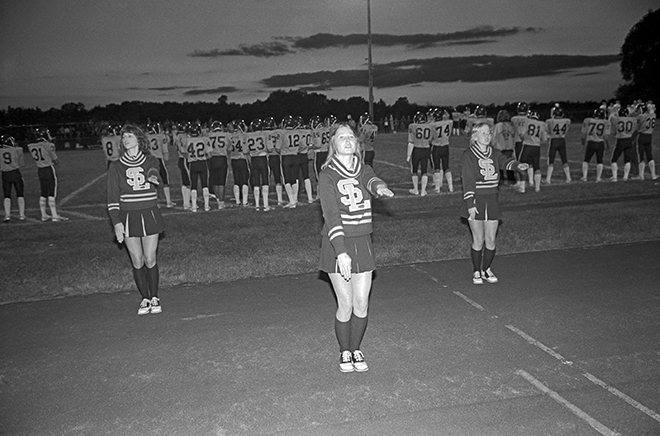

To celebrate the release of Twin issue 12 we have teamed up with American-made goods company Shinola to present the striking work of Detroit-born photographer Don Hudson, including previously unseen images. The 12th edition of Twin is all about attitude, and Hudson’s powerfully candid images are testament to the playful, tough and collective attitude of the long troubled Detroit and its surrounding areas.

Hudson’s photography naturally resonates with Shinola, a company that is deeply embedded in the city of Detroit. They are committed to returning some of Motor City’s former industry glory by choosing it as the location for producing their handmade watches and bicycles. Shinola has created local jobs and cultivated new expertise, building a strong sense of community and renewed pride in American craftsmanship.

Following in the footsteps of the likes of Gary Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and Robert Frank, Hudson’s photographs, taken during the 1970s, are a time capsule of American life from his point of view. Shooting at local fairs, rodeos, carnivals and parades, Hudson captured moments of communities coming together for a fleeting but all too important moment of carefree fun.

Here Don Hudson tells of how his love for photography developed, why he describes himself as ‘proudly amateur’, and what he wants to capture when he looks through the lens.

I was born in Detroit but grew up nearby, in a little town called Plymouth on the edge of Wayne County. The seed for my interest in photography was planted when I was a kid, when I was the one being photographed. I grew up in the 1950s and when the camera came out we became subjects, we had a certain place to stand, to look. Thinking back, the idea of the camera as a transformative machine must have lodged itself in my subconscious back then. My interest in it really took off when I got to high school age. I had a couple of friends who ran the yearbook and had built darkrooms, so I jumped in with both feet. I built my first darkroom in my mother’s laundry room—it was kind of a set-up, known-down construction on top of her washer and dryer, with the windows all taped up. I was fascinated by the magic of the darkroom.

Then I graduated from high school and went on to university, but I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I spent three years doing a Liberal Arts degree and drifting more or less, then in 1972 I decided that the only thing I really liked to do was photography, so I applied to an art school in Detroit, CCS (College for Creative Studies)—it’s funny because I recently realised that Shinola actually have their watch factory on the campus. I really delved into the technique there, I learned the zone system, I became a lot better technically. I was also exposed to the history of photography and came into contact with more people who were into doing the same thing I was. During that period what solidified in me—getting back to the power of the camera—was having a huge amount of respect for how the camera sees things. I want to let the lens record as much information as it can. My whole thing—the only thing I was interested in—was what was coming straight out of the camera.

The photographs that are in my book, From the Archives, were taken during the Seventies, which is when I was coming of age photographically. Lee Frielander and Garry Winograd were coming out with their books at that time, and a few of my friends and I looked their work and thought that’s it. They were in the generation preceding us and what we wanted to do was in reaction to what they were doing. That approach which looks like documentary photography, it’s very straight, but it’s basically documenting your own relationship to your culture through photographs.

A lot of what I shot was public events. I searched out parades, carnivals, festivals, fairs, rodeos—places where there was a lot of social energy going on. I spent four years photographing high school football games. Every Friday night the community was all about the football game.

I describe myself as proudly amateur because I took photographs purely for the love of it, there was never a commercial aspect to my work and no ambition in that regard. I’m lousy with self-promotion; I’m just not a person who can do it. I’m going to do this regardless of whatever popularity may come of it.

I think of photographs like this: they look like the truth, I approach them with a high degree of respect for the way the camera sees things, but whatever I decide to put four edges around is always going to put the scene into a questionable context. They look like the truth, but what is the real meaning of the image? You don’t know what came before that moment, you don’t know what’s coming after that moment, all you’re seeing is one little facet of time and space. That’s what’s cool about photography too; it’s intimately involved with the sense of time. I think it was Winogrand who said photographs are like new facts. They’re new facts about life. Over time there’s a certain power that the photographic image gathers, and I’m enjoying that now, whatever small ripples these photographs may be making.

shinola.com

Tags: Shinola, Twin XII

13.05.2015 | Art , Culture , Music | BY: Clementine De Pressigny

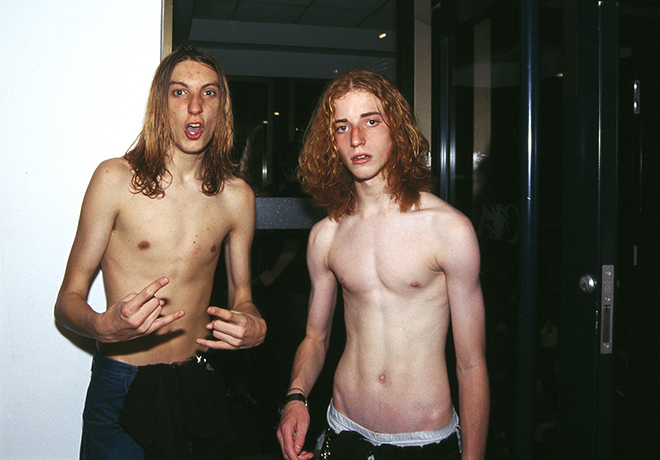

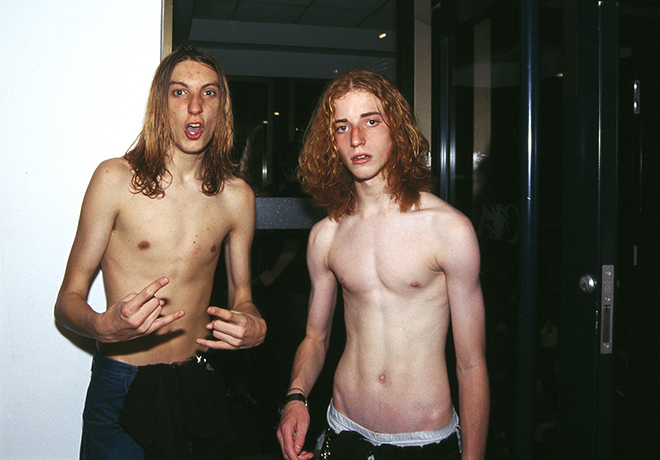

London photographer Sanna Charles has been shooting those who worship at the alter of Slayer for over ten years. Her recently published book, God Listens to Slayer, documents the ritualistic devotion of fans around the world to their musical deities. Flicking through its pages is to be transported to a hot, dusty metal festival, to feel the feverish anticipation before the band shows, the crush of uncoiled bodies in the mosh pit, and the calmer moments afterwards when the communion of fandom lingers. We caught up with Charles to find out how her striking book came about.

When did you first get into photography?

My Dad was a photographer, we always had cameras around and he got me one when I was quite young. I started learning about it while I was at school, then I went to University in Brighton to study it there. Initially I was doing a lot of architectural stuff—I would come back into London and take photos of urban landscapes that were quite stark and bleak. But I was always into music, so after I moved back to London I started photographing the rock and roll and punk scene. Then I got picked up by NME, so I kind of fell into music photography.

And it was while you were working for NME that you started shooting Slayer fans?

Yeah, it happened while I was on assignment at Download festival for them.

How did the project start, did you set out to shoot Slayer fans or did it evolve more naturally over time?

It definitely happened more naturally. It’s funny, when you’re on a job shooting a festival like that, you’ve got your list of bands, there is always a lot of running around to do, but in the quiet moments you’ve still got shooting in your head. I think I took about four of five pictures of Slayer fans at that festival. There was a group of guys running to get to the tent where they were playing, and I asked them to stop. I just really liked the excitement that they had at that moment in time, and I was trying to capture their energy. NME didn’t want to use those pictures; they weren’t really into documentary style at that time. But I kept hold of them and I felt like it could be the start of something. I was living with a filmmaker friend at the time, she had a car and we decided to just take off and follow Slayer on tour. We spent loads of money that took years to pay back.

Why do you think Slayer elicits such intense dedication among fans?

I think there is a mixture of reasons. When Slayer first started there was really an appreciation among their fans of being given a way to release aggression just by listening to the music—and watching them if they could. And the band hasn’t really changed, they have a formula that people love and they stick to it, they don’t alter according to fashions or tastes. Also, they created this genre, the speed metal, thrash style—it wasn’t really around anywhere else at the time, and people really appreciate that. It’s like an artist who starts a movement, or a film director who creates a certain style. Slayer took a real risk making music like that, and they were lucky that they exploded.

What was it like for you as a female photographer in the still very male-dominated world of metal?

You know, you get slimy comments sometimes, but I think generally as a female you get used to that in any environment and you build up a tolerance and know how to respond. In a festival environment most of the time you’re going to laugh it off, because it’s not worth it, and I was trying to get a picture.

A couple of photographs in the book are of girls. How do they fit into the world of Slayer fandom?

Sometimes girls who are into metal can be a bit harder than guys, they have their guard up because there’s not many of them. But once you start having a conversation then there’s a really nice mutual respect, you’re there for the same reason. There’s an unspoken thing that you get it.

God Listens to Slayer by Sanna Charles is published by Ditto Press and is available to buy now.

dittopress.co.uk

Tags: photography, Sanna Charles, Slayer

Twitter

Twitter

Tumblr

Tumblr

YouTube

YouTube

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram