The phrase ‘high-tech’ makes most of us think about phones, computers or intelligent dishwashers. But it’s one that makes some architects gasp with indignation. This year the Sainsbury Centre celebrates its 40th anniversary with “Superstructures: The new architecture 1960–90”. An exhibition that picks apart the architectural movement behind the centre itself and examines the controversial label of ‘high-tech’ against the wider architectural canon.

‘High-tech’ architecture was championed by legendary British architects Norman Foster (the designer behind the Sainsbury Centre) and Richard Rogers (Centre Pompidou), amongst others. This group of architects found ideas of adaptable, expandable and mobile buildings exciting. They were interested in pragmatic solutions, and inspired by earlier architectural ideas and innovations like Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes and Jéan Proves demountable house.

Current day Sainsbury Centre 2009 | Photo:© Sainsbury Centre, Pete Huggins

The high-tech style managed to blend post-war 60s utopian ideas with 19th, and early 20th century ideas about adapted architecture – a mixture that resulted in expressive and very characteristic buildings. It was a technologically focused – one might even say obsessed – development from modernism.

Talking via a malfunctioning, ironically un-high-tech Skype connection, Twin chatted with curators of the exhibition Jane Pavitt and Abraham Thomas. An era of optimistic architecture that looked to engineering and technology for new possibilities certainly seems resonant in 2018.

Sainsbury Centre construction 1975 – 1978 | Photo: © Foster + Partners, Alan Howard

Could you begin by telling me a little bit about the exhibition?

Jane Pavitt: The exhibition is about this crux in late modernism, the term often used in association with it is high-tech. We have taken a rather interesting positioning I suppose… In the exhibition we show the long history of association between technology, engineering and architecture. It starts with the the Sainsbury Centre, a superstructure that is, in a sense, an enormous shed. It’s complex, beautiful, precisely engineered, but still kind of like a shed.

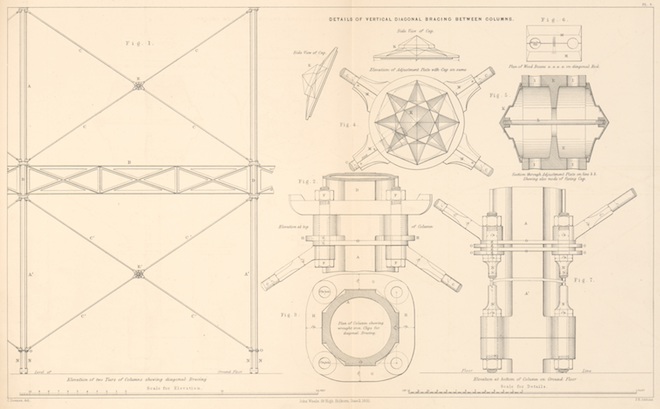

We used this building to explain the high-tech approach to architecture. Then we look at ground structures like the Crystal Palace, and through to the modern experiments by Prouvé and Buckminster Fuller. Finally we look at the generation of architects that we are focused on. The first part of the exhibition tell the pre-history, then we get to high-tech it self.

Abraham Thomas: Should I go back to high-tech?

Jane: Yes, I see that she’s dying to hear about it.

Abraham: One of the things that we wrestled with as curators is using the phrase high-tech without actually using the phrase high-tech. The term is very divisive, a bit like postmodernism. Many of the practitioners of postmodernism hate that label. Jane curated the big postmodernism exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum so she has been through this.

Jane: [laughs] The toxic term.

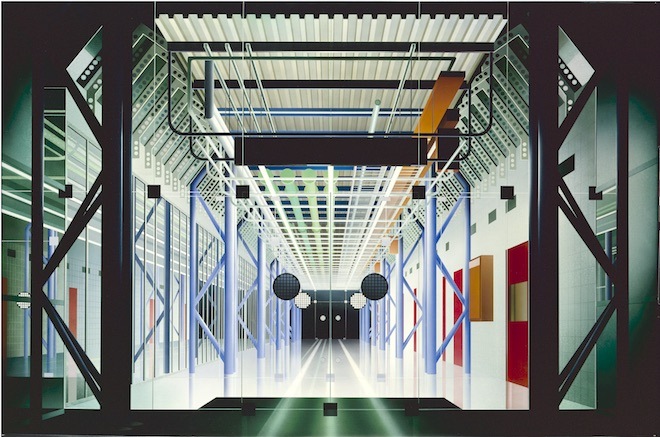

Ben Johnson, Inmos Central Spine, 1985Acrylic on canvas | © Ben Johnson

Abraham: We had to be conscious to the fact that many of these leading architects absolutely reject the term high-tech. It is reasonable to an extent, they reject it simply being a style. What we are trying to say is that it was more than a style. It was a sort of ethos, a movement. But it is a convenient term, it refers to the idea of influence of technology. In a way it is valid. But we also sort of pick it apart, don’t we?

Jane: We wanted to make it very clear that it’s certainly not a style label, although it’s often used like that. These buildings are stylistically very different. The architects reached different types of solutions, but they all share a set of principles. The Sainsbury Centre and the Pompidou Centre are totally different solutions to the same set of ideas and concerns. They respond to their sites, position and purpose in different ways. On the other hand, we felt as curators, and historians, that if there is a term that has some currency historically – it is a frequently used label in architectural history – then this is the right time to kind of, as Abraham says, pick it apart and attempt a much more nuanced understanding.

Do you think there is another term that could work better?

Jane: Architecture of advanced engineering is a good description. That’s what they are concerned with, testing the limits of certain kind of building methods. If you think of high-tech as a process, rather than a style, that’s quite a useful way of approaching it. I would say that it’s a type of technological modernism.

But people like labels, don’t they? Like art deco. Everybody has contested the meaning of art deco, but it is still a very powerful term. Postmodernism is a term that makes people angry [laughs] but it persists. Rather than abandon the label all together, we wanted to unpack and position it. These buildings share certain things about advanced engineering and precision engineering, but they can also be simple solutions.

To take an example: we have reconstructed a section of Michael and Patty Hopkins house in the exhibition. It is not high-tech in that sense. It is appropriate technology. They liked the idea of using pre-fabricated components and cost effective materials that could be assembled simply, cheaply, effectively with a powerful aesthetic.

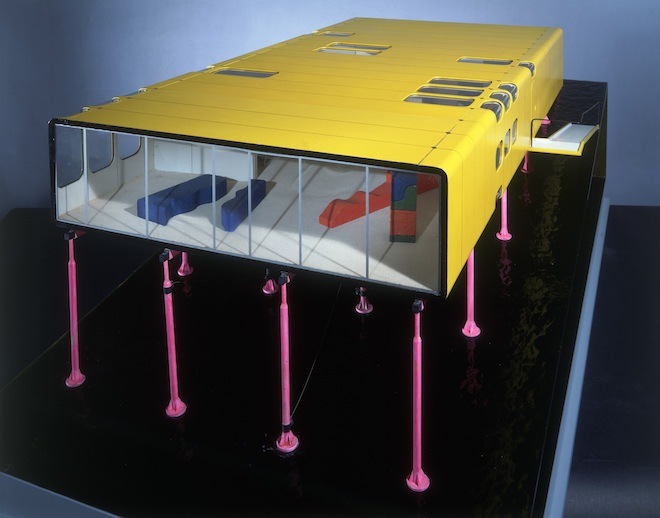

ZipUp HouseDetail colour presentation competition model, scale 1:20 | Photo: © Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, Eamonn O’Mahony

Abraham: There are a number of examples of high-tech buildings with ideas from other explicitly progressive technological contexts. For example, here at the Sainsbury Centre, Foster created a double skinned wall which allows a lot of the servicing and utilities to be packed away, resulting in this sleek exterior surface and an uninterrupted interior space well suited for an exhibition layout. That idea came from Foster’s observations of a passenger aircraft, were you have a sort of false elevated floor where all the services can be packed underneath.

Jane: There is this section in the exhibition where we have some of the original cladding from the Sainsbury Centre next to a part from a [Citroën] 2CV van. Those ribbed aluminium panels that slot into a car are remarkably like the panels that clad this building. The term high-tech is a bit forbidding, but these buildings have almost the childhood appeal of assembling models.

Abraham: Jane’s point immediately makes me think of this amazing object in the exhibition, a project called Tomigaya. It is a mixed use, residential and cultural space in Tokyo, and the model is made from Meccano. It’s a slightly lighthearted moment in the exhibition. The model of Tomigaya encapsulates a rare notion of simplicity, an understanding of how buildings are put together. It makes it very accessible.

Crystal Palace details of bracing between columns | Photo: © Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851

What drew you to this project at first?

Jane: The Sainsbury is one of Britain’s best postwar buildings and it is extraordinarily powerful. It attracted a huge amount of controversy, admiration and criticism at the time it opened. It’s been fascinating to re-examine that. This group of architects are among the most prominent in the world and produce buildings in all typologies: office buildings, factory buildings, buildings for culture, domestic projects, airports, stations. In London, especially in transit, we all move through these buildings. You probably could encounter a Foster, Rogers, a Grimshaw building within any square mile of central London.

Abraham: I went through Heathrow today and the Rogers’ Terminal 5 has a lot of expressive engineering.

What would you say was most challenging with this exhibition? There are so many different aspects to it.

Abraham: I think it’s always tricky when you’re a temporary guardian of someone’s legacy. These are all very successful architects now, huge international names.

Jean Prouvé House, France | Photo: © Galerie Patrick Seguin and Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

And still alive!

Abraham: Yes they are all still alive! You’ve got to be really careful with how you present that legacy. That is always the case when you’re working with any contemporary artist or architect, but I think that is particularly the case here.

One of the hardest things was to ensure that we were sensitive to their legacies, but also created a new narrative. Since the mid 80s there have been shows on these key British architects – Jane and I didn’t want to do another “Best of British Architects” exhibition.

Jane: It’s not a biography show. Architecture exhibitions are difficult. A lot of visitors may not be familiar with reading architectural plans and some of the buildings will be unfamiliar to them. We wanted to explain how buildings worked and how they were made. We’ve just come back from installing two giant wooden carved prototypes of the steel joints from Waterloo International Station. They are about a meter or so high, but fantastic objects. Like pieces of sculpture.The process of construction is fascinating for people of all ages, we are just trying to emphasise that.

SUPERSTRUCTURES: The New Architecture 1960 – 1990 is on at The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts 24 March – 2 September 2018

Feature image credit: Century Tower, Japan | Photo: © Foster + Partners, Saturo Mishima

PREVIOUS

PREVIOUS

Twitter

Twitter

Tumblr

Tumblr

YouTube

YouTube

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram