18.09.2019 | Blog , Fashion | BY: admin

Images courtesy of Simon Melber

The world is a scary place at the moment. And this season, fashion has taken notice. Designers have been either making open political statements through their clothing or indulging in an escapist mode by presenting bold garments which express their need to run away to distant lands. British-Canadian designer Edeline Lee is very aware of it, and that’s exactly why her Spring Summer 2020 collection was a light, brightly coloured burst of joy.

This season, the designer wanted to inject a bit of optimism in her clothing, as past season’s fall-winter 2019 presentation had such a tough subject matter (she had been inspired by professor Mary Beard’s feminist manifesto, Women & Power, where Lee made the case for the runway as soapbox).

“I feel like we need a bit of optimism right now and so I felt like I needed something light which could contrast the darkness of everything that’s been going on at the moment,” she said.

Following up from her experiential presentation of last season, this time Lee collaborated with Sharon Horgan, the Irish actress and writer who starred and co-wrote Catastrophe and created HBO’s Divorce, for a presentation which verged on the line between theatre and runway.

“Sharon and I are friends but not only that. I am such a big fan of her work, her voice and the way she talks about the human condition is so acute and real and to the skin,” she says.

And the clothes she presented exuded exactly the same vibe, they were real clothes for real women, which featured simple silhouettes – ranging from a series of white shirts and brightly coloured midi dresses in a palette of greens, blues and reds, to a series of brightly coloured striped numbers, to finally, a series of dresses made in her signature jacquard.

“In the show in a way what we’re trying to do is juxtapose the lightness of the clothes to these real-life moments which are acted out by a series of actresses, who sort of stop and get distracted by real-life passing by and then they stop and go back to their intimate realities,” she says. “It’s sort of like a play on a juxtaposition of these different versions of life.”

Sitting in one spot over the course of 15 minutes you would be able to experience every skit presented by the actresses almost as if eavesdropping on conversations of everyday life.

Lee’s collaboration was a refreshing take on a runway experience – and it definitely helped her in trying to represent who her woman really is and making people understand who she’s making her clothes for and the audience she’s making it for. Collaborations like these are a fun way to get the point across and are also more memorable experiences in a month where editors see an enormous quantity of shows.

Tags: collection, designer, edeline lee, Fashion, london fashion week, ss2020, Twin interview, Womenswear

30.05.2018 | Music | BY: admin

The moral of Poison Arrow’s hypnotic and addictive debut EP, Pleasure District 007, is don’t mess with a woman’s emotions. The title track ‘If You Don’t Love Me’ continues with the lyrics: I’ll cut your face with a razor blade that I use to shave my legs. Poison Arrow, the alter ego of DJ and producer, Natalia Escobar, talks to Twin about the influence of her native Colombia, women in music and telling stories.

What are feels about how Colombia is presented and how did you want to twist that?

I mean, it’s time that people know Colombia for something else apart of Narcos and Shakira. It is such a beautiful and rich country, naturally and culturally. There are so many talented people doing great projects. I wanted to showcase some of this.

I’ve lived in many different countries and travelled a lot, so my music has a lot of different influences, yet I wanted to do a modern interpretation of Carrilera’s unique cultural heritage musically and visually. For example, I worked with House Of Tupamaras, which is the first Voguing house in Colombia. They are so good and they Vogue to traditional Latin American music. We used Voguing as a tool to tell the story of “La Cuchilla” combined with some folkloric machete dancers and with the Hermanitas themselves – who are the biggest proponents of this genre.

What are your feelings about Colombian concept of female power?

I believe Colombian women have “malicia indigena” which means a positive kind of awareness, intuition and smartness that the indigenous peoples of Colombia possess. This makes us powerful!

The Colombian conflict has affected women in a lot of terrible ways. But the FARC – the oldest armed rebel group – was just disarmed and the country is going through a big transformation. From the guerrilla reintegration into society, to women not seeing themselves as victims but affirming their rights as citizens, things are changing.

The upcoming elections are very important for the future of the peace agreement. It is good to see that almost all the candidates for the vice presidency are very well prepared and strong women. It’s a crucial moment to heal wounds and empower ourselves to rewrite history.

With my narrative in particular, I am trying to put the listener under a spell through personal situations.

If You Don’t Love Me (I’ll Cut Your Face) from Poison Arrow on Vimeo.

What do you like about songs with a narrative?

I believe music is the most powerful storytelling tool. Whether it’s through the voice or a melody, music is always telling a story. The beauty of it is that we can’t rationalize it but we feel it.

Current inspirations and influences?

Cosey Fanni Tutti’s art and music have always been one of my biggest inspirations. Now that I just finished reading her autobiography, I am more inspired than ever.

Follow @poison.arrow on Instagram and find out more about the record here.

Tags: Feminism, Poison Arrow, Twin interview

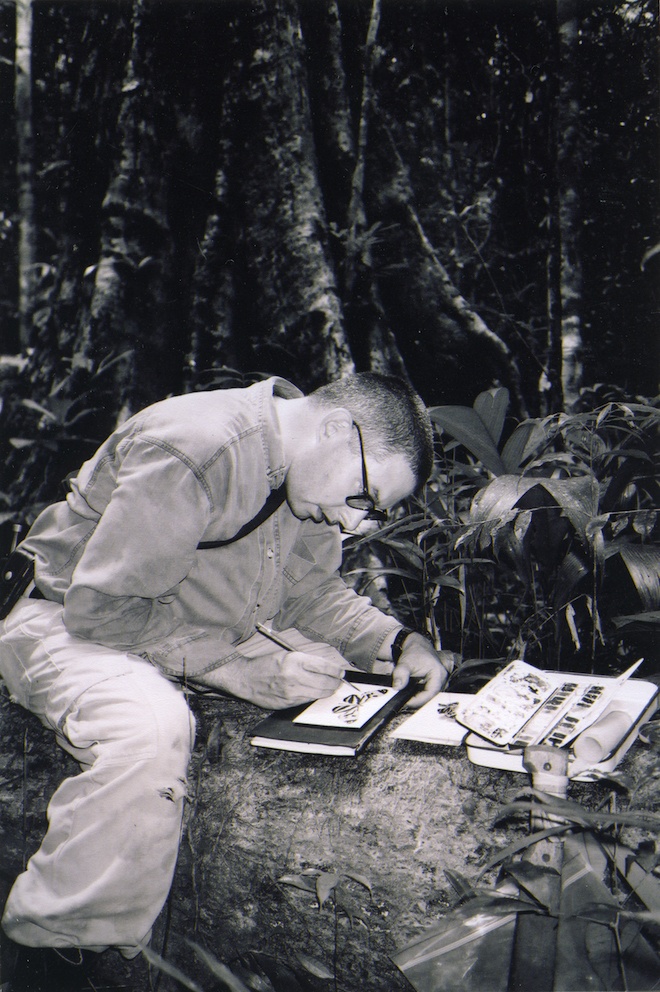

26.04.2018 | Art , Blog , Culture | BY: Thomas Rackowe-Cork

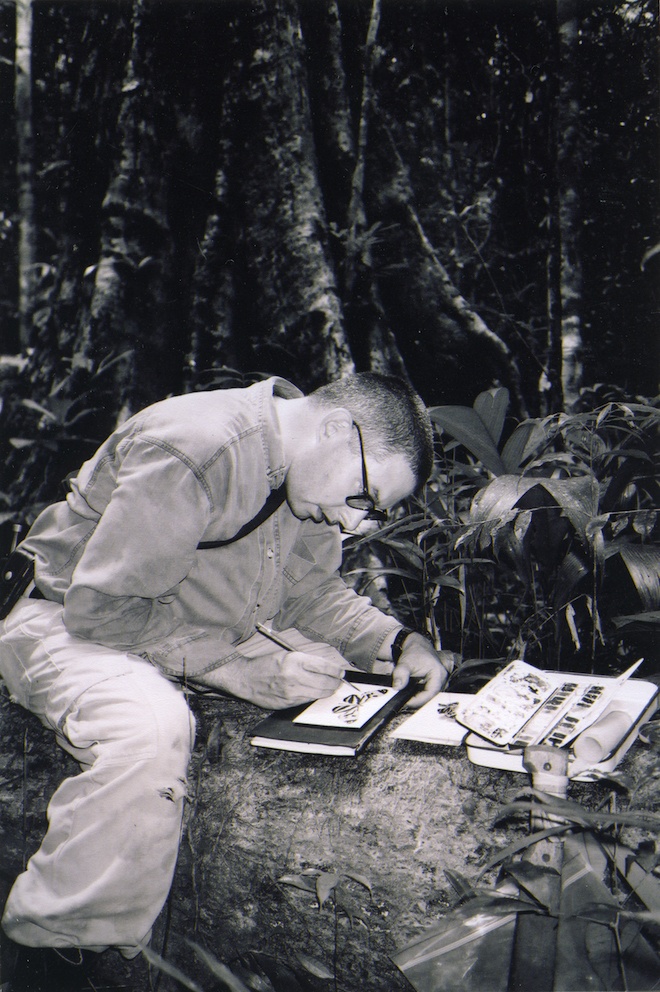

The nature-culture dualism is central to the work of American artist, Mark Dion. Best known for his immersive sculptures and installations, his work examines how knowledge is gathered, interpreted, classified and presented. For his solo exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, Dion examines our complicated – and conflicted relationship – with the natural world raising questions concerning the culture of nature and the environment. Twin spoke to Mark and The Whitechapel Gallery’s director, Iwona Blazwick to talk about the major exhibition, its curation and the ethical duties of artists and curators.

Thomas Rackowe-Cork (to director IWONA BLAZWICK): What initially drew you to Mark’s work?

IWONA BLAZWICK: I first encountered the work of Mark Dion in a gallery in New York in 1990. Marching across the white cube space was a line of wheelbarrows filled with exotic pot plants and cuddly animal toys. It was called ‘The Wheelbarrows of Progress’. It struck me that here was the legacy of minimalism but infused with narrative, politics and humour.

TRC to curator IWONA BLAZWICK: Can you tell me about the curation for this exhibition? Is there a particular circulation you had in mind for the viewer to experience the exhibition?

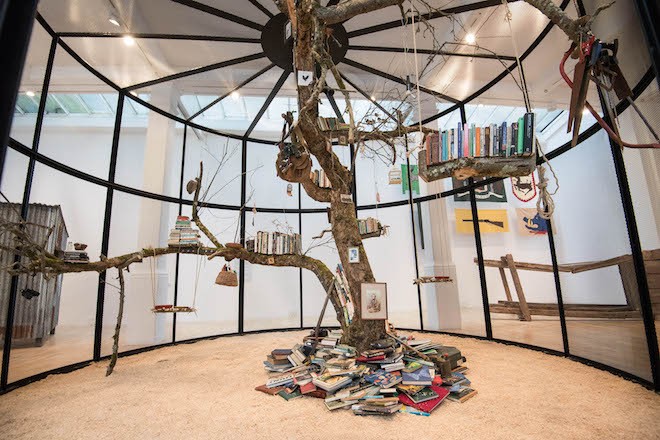

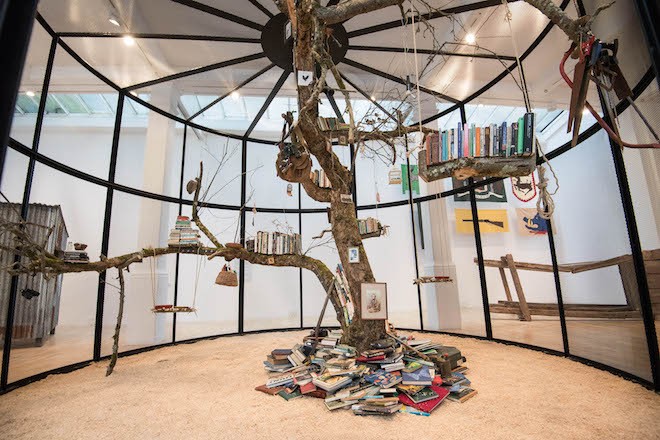

IWONA: Mark Dion is a scenographer and explorer. So, our curatorial approach was to take the viewer on a journey through a series of visual adventures. The voyage starts with life – 22 zebra finches in their beautiful Library for the Birds – proceeds through an expertly camouflaged yet hostile series of structures made for observation and hunting, through a studio for the contemplation of nature, an uncanny museum display and an archaeological dig; it ends with death in a room of ghosts glowing in the dark.

TRC to artist MARK DION: What drew you to the world of natural history and science as a mode of investigation?

MARK DION: I think one of the things that drew me to the world of natural history is that it is a field where we are asking exciting questions; who are we? Where do we fit into the world? What is the world? How did we get here? Conversely, I find the art museum asks questions of value and aesthetics – areas that were not especially inspiring to me. So, on the other hand, these institutions, such as museums of natural history and ethnography museums, tend to both ask questions and give answers. They turn the viewer into a passive viewer. Whereas the art museum has a very critical view – they don’t expect that you necessarily agree with the work of art. It is almost encouraged that you do not. So, I wanted to bring those two worlds together. But my principle motivation is a kind of love for nature and experiences and it is something that was always a big part of my life growing up and I can’t imagine it ever not being a part of my life. And with growing up in the city, you search for surrogates – you may not be able to get to the mountains every weekend or to the coast. But you can get to the natural history museum or the park.

‘The Library for the Birds of London’ on show in Mark Dion: Theatre of the Natural World | © Jeff Spicer/PA Wire

TRC: The cabinet of curiosities is a theme that you repeatedly revisit in your practice – could you tell me a little bit more about why that is?

MARK DION: My interest was really in wildlife conservation and biodiversity. That brought me to the museum and then as I became closer to the museum, I became closer to its history for the collections. It was here that I discovered the tradition of the Wunderkabinet, which later peaked my interest in the 16th and 17th century collections. I found these collections really interesting because they contrasted so significantly from the imperial or colonial collections as they were not something of national prominence or filled with ideology. Rather, they are highly individual cosmologies. Though they are undoubtedly related to colonial processes, they are not the colonial museum in the same way. They are as much proto-scientific as they are spaces of magic, religion and superstition. So, that kind of mixture and hybridity, not only of the objects, but of their meaning as well, is important in thinking about how we move forward in terms of museum design – looking to the past and looking to the unexpected way things are put together.

TRC: The nature of a cabinets of curiosity seems to be concerned with collecting and classifying. Do you have a theme in mind when you collecting or making these material objects?

MARK DION: Very often, I go back to their original methodology where you would use an allegorical structure. I think that in trying to reconstruct those you have to also try to put yourself in the head of a maker from that time. So, you are intentionally putting things together that we may not put together today. So, let’s say, if you are using the elements of the seasons and you are putting them together based on the idea of fire, I try to ask myself; what does that necessarily mean? So, I find that really exciting.

TRC: So, you do not approach the curation of these cabinets thematically – could say then the curation is more intuitive?

MARK DION: Well I’m thinking about the themes that would exist in a historical setting and trying to mirror or refresh those. So, I am constantly thinking about their allegories. Very often, I look back at young Bruegel paintings, for instance, or something like that as a way of imagining what does the allegorical air look like?

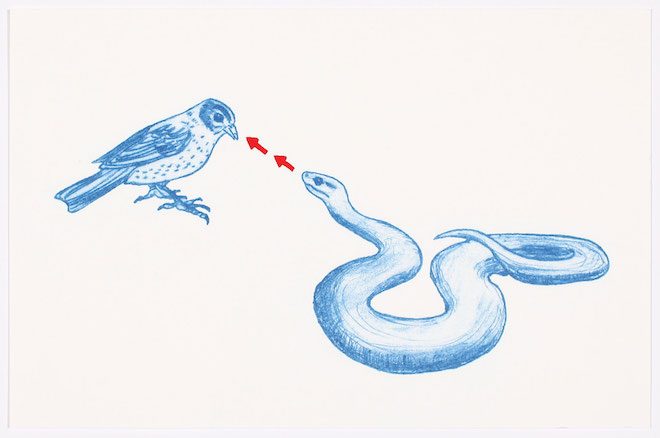

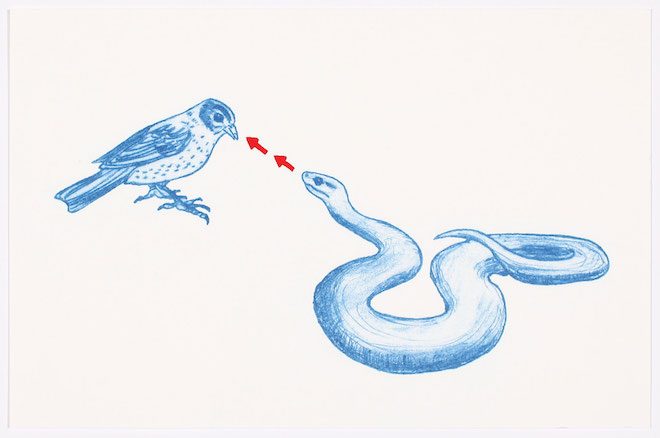

Mark Dion ‘World in a Box’, 2015 | image courtesy of Whitechapel Gallery

TRC to IWONA BLAZWICK: The cabinets of curiosities are already curated in a way – how do you go about curating the cabinets themselves?

IWONA: The artist makes his own cabinets of curiosity – our role is to immerse our visitors in them, encouraging them to act as detectives searching for the myriad clues embedded in Dion’s assemblages, drawings and wallpapers.

TRC to MARK DION: From the sort of themes that you are looking at; what are some of the most fascinating objects you’ve found over the years?

MARK DION: There are always found objects that you pull out of rivers and one of the most interesting things about creating pieces for this exhibition was that I was working with people that were not trained as archaeologists or artists. It was interesting to see how some of which had a very accentuated search image. Whilst others had a really difficult time just seeing. As for me, one of the most exciting things we found were those traditional objects that you embellish with cultural artefacts. For example, you may have a whale’s tooth and surround it with silver and engrave on it. The opposite of that might be a cultural object that is traced with worm tracings or oyster shells or slipper shells and things like that. Things that articulate that opposite. In many cases, I found it interesting that many of the young people working on these projects were entirely unable to tell the difference between a rock of flint and a cultural object. To them, it seemed unfathomable that a piece flint, for example, was not human made because the natural world just does not make something that strange. So, these things that articulate the natural affecting the artificial I see as bookending the cabinet of curiosities and accentuating the natural with the artificial.

TRC: Following on from that, do you think our relationship to a found object changes when placed behind glass?

MARK DION: Oh, absolutely. It changes over a period of time. For example, an artist like Robert Rauschenberg might find a glue into a collage a newspaper cutting from his day in 1953. Suddenly, today that is a very exotic newspaper, with a different time sensibility, and different make up. So, not only do they change by this process of becoming “museum-ified” but they also change dramatically just by getting a little bit older. Even with things here in the Thames Cabinet from the dig in 1999 here in the exhibition, someone was looking at them yesterday saying “Oh! SunnyDelight – does that still exist?”

TRC: Do you think that these found object lose some agency when they are placed in this context?

MARK DION: I do not think they loose agency. In fact, I think that they gain some agency, or the viewer gains some agency because they begin to see themselves in this context. What is important for me about the Tate Thames Dig (1999) is that people find themselves in it. It is not this notion that history happens to someone else, sometime ago. Rather, it is a continuity that is inclusive. We find ourselves in that, which also implies that this history goes beyond us. One of the most difficult things we face as a society, is this ability to imagine things going on beyond us. I feel that is why many seem not to care about leaving behind a mess.

Mark Dion exhibition | courtesy Kunstraum Dornbirn

TRC: Yes, it is incredibly hard to fathom the sort of everlasting element of material objects… the idea that things can live beyond us…

MARK DION: Absolutely. We are just a point in the continuum. And so that is sort of my real agenda with these pieces to emphasise this notion of a continuum. For that to happen, the viewer has to find something that they have touched, something that they know or are familiar with.

TRC: I sort of felt a sense of nostalgia whilst walking around the exhibition – would you say that this feeling or emotion plays a somewhat central role in your work?

MARK DION: I am always trying to guard against nostalgia. But at the same time, I think that I certainly have an affinity to materials that are well-made – that are crafted in leather and wood rather than in plastic. At the same time, I try to police myself against this golden ageing. It is the curse of nostalgia to imagine the past is somehow a purer, a better or a more superior time, which it clearly was not at least it was not for many of us. It would always feel artificial, for example, to place a laptop into a study of surrealism. I mean, that is not a good example, because the piece Bureau of the Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacy (2005) in this exhibition is a period piece that is meant to be a 1923 office.

TRC: Is there a hope to achieve anything by bringing these things back to the surface?

MARK DION: I want to cultivate the viewer who is more cautious and sophisticated. But at the same I want to be critical and to that you have to be affirmative. That is to say, to affirm people’s world views so you don’t feel entirely isolated – that you’re not the only one on the right road.

TRC: How do you think artists and have ethical duty or responsibility to bring certain issues to the surface?

MARK DION: I would not want to be prescriptive, but for me it is important. I mean, otherwise I wouldn’t really understand what the point of making are would be. I could understand why someone would want to make work as a self-expressive gesture, but I just do not understand why they would think an audience would only need to see that. I am interested in artists who are not afraid to have a didactic aspect to their work. Who are not afraid to say something and to have a position. That is the kind of art I like. So, I am not afraid to make that kind of art myself. At the same time, we have to face a lot of this stuff in society anyway, which is not particularly successful in terms of messaging. So, I wonder how to do that with complexity. I think for me, humour is part of the way to do that and also just trying to do things really well that builds a confidence in the viewer that is worth engaging with.

TRC: How do you think curators have ethical duty or responsibility to bring certain issues to the surface? Here for instance, the conservation of the environment.

IWONA BLAZWICK: The curatorial mission changes according to its institutional and social context. For us at the Whitechapel Gallery we are dedicated to offering a platform for contemporary artists – and they don’t have a duty to comment on issues. While World War II raged about him Morandi just continued to paint bottles. He is nonetheless a great artist. However, an artist like Mark Dion is exciting because he is able to respond to the environmental crisis in a way which combines ethics with aesthetics. He has spoken of his despair at our indifference to the fate of our planet – but I see this exhibition as being full of hope, making us reflect on our relations with other species while rekindling our sense of awe at the natural world.

Mark Dion ‘Theatre of the Natural World’ is on at the Whitechapel Gallery in London until 13th May 2018.

Featured image credit: Mark Dion in the rainforest of Guyana | Photo by Bob Braine, courtesy of Whitechapel Gallery

Tags: Mark Dion, Twin interview, Whitechapel Gallery

05.04.2018 | Art , Blog , Culture , Fashion | BY: admin

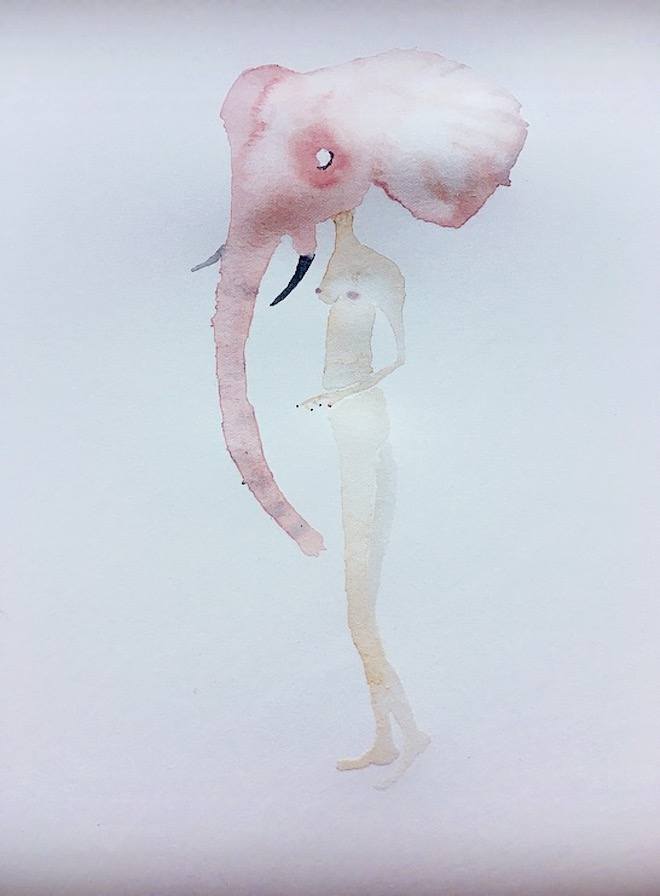

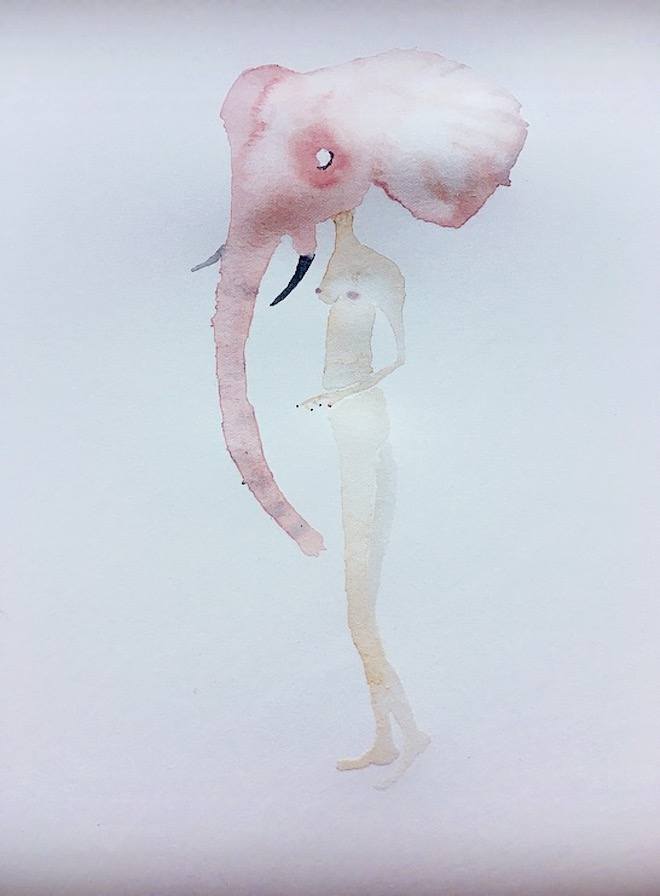

New York-based designer Alice Waese offers textured, evocative design across jewellery, clothes and illustration. Her work is sensual and imaginative, imbuing those who wear or otherwise engage with her work with a sense of heightened or unexpected reality. Twin caught up with Alice to talk about her work and her creative process.

You work across a range of mediums. Where did you start?

I began with drawing as a kid, chalk, paint then pencil, then pen, then watercolour.

In terms of jewellery, what are the most challenging materials you’ve worked with?

Casting fine leaves, snake skin, leather with lots of undercuts, a round pinecone.

Which materials and / or stones do you find most interesting, why?

This season I am really interested in pearls because of how they form, The crustaceans coat an intrusion, something foreign, something parasitic enters the body and in an effort to protect themselves they coat it, creating something beautiful.

You often include small figures or body parts in your jewellery designs. Why did you decide to use these?

The figures and body parts relate to a series of drawings where I was really studying the body in relation to the non material world. the severed limbs related to a series of paintings where body parts were energetically connected to other parts with a thin red line of paint. I then sculpted them in wax and stung them on chain, it came naturally, tells a story and relates to the themes I was working with in my drawings at the time.

Why was it important to have a sense of texture and materiality in your work?

I think the textural component comes from a reflection of what I find visually interesting the world, it is less an importance or a decision, and more following an intuition and staying true to it. I think texture and imperfection translated into a precious metal that is usually smoothed to perfection creates an interesting juxtaposition.

How does your design approach differ between jewellery and clothes?

Its actually a very similar approach. Never a mood board or a singular inspiration, more an internal concept, a series of paintings, a texture, or a new process I am experimenting with, often the outcome of a mistake.

Did you find that it was easy to translate your aesthetic throughout the range of works?

I don’t find it difficult to speak through different mediums, being honest with my process and limitations and creativity makes it easy for the same voice to pass through.

Watercolours have quite a different quality to the materials you use for clothes and jewellery. Why did you decide to work with watercolours for your illustrations?

I like the fluidity of watercolours, it allows me to make up the rules as I go along. The process is similar to how I work in jewellery and clothing.

When starting a project, how does your creative process begin?

Its not a set regime, always different, but usually a clear need to make something.

What would you say are the most powerful informants of your work?

Whatever mistake I just corrected or embraced usually informs the next piece of work.

Tags: Feminism, Twin interview, Twin meets Alice Waese

10.11.2017 | Blog , Fashion | BY: admin

Amélie Pichard celebrates sexy. Her shoe brand does too. Presented with her footwear, you meet a brand that has titillating sensuality at the core, partnered with the somewhat odd bedfellow of comfort – not necessarily a predictable alignment but refreshing nonetheless. Here is someone who is making a damn good stab at constructing the feeling of sexy, rather than simply the look of it. Aiming to exact empowerment and pleasure to women through artisanal technique and a certain retrograde sensibility, Amélie has opened her first shop, in the wake of her successful online business and a celebrated Pamela Anderson collaboration. Locking herself into bricks and mortar signals something new for the Parisian designer: cementing herself as part of the modern heritage of her city. Amélie wishes to be the female version of Hugh Hefner, to praise the natural sensuality of women. Her aim? To herald the woman: to celebrate sexy for the self.

AMÉLIE PICHARD / RECLUSE from BERTRAND LE PLUARD on Vimeo.

Who is the Amélie Pichard woman?

She is free. This is the very first thing to realise. My girls, the Pichard girls, know what they want, when they want. I don’t do things because there are rules – I don’t care about that. Pamela Anderson was my first muse: for me she is the perfect Pichard girl because she is complex, a woman, a mother, an activist, a girl boss: exactly what I love. I don’t like girls who don’t work. What does sexy mean to you? Sexy for me is everything. For me it is so important, but it must be a natural sexy – it’s not about clothes or makeup, it is about attitude. When I look at your shoes, it is like you are trying to change what sexy means, and twist how it is traditionally a male-dominated word. Your brand seems sexy for itself… Before, to be sexy, women wanted very high heels. For me it is the opposite, because if you cannot walk properly because of your shoes, you are not sexy. For me, women wearing trainers can be more sexy than women who can’t walk in their high heels. I do shoes for the girl who has her bicycle, who needs to go food shopping, who needs to live and work.

What type of atmosphere are you trying to create in your new shop?

In my shop, it is a lot of things, because I am obsessed with Hugh Hefner – I want to be the female version! I want the most beautiful guys working in my shop, at the door of chez Pichard. I put a bed in the shop because I wanted to make a shop not just for shoes: a place where people can stay and live, chill, and the bed was the way of doing this. The shop is a mix of the 70’s and a bar tabac, because the French spirit is very casual, and I also love contrast. That is why the front of the shop is green, like the bars of Paris, while inside the first thing you see is a bed dressed in Pink, in varying textures.

Amelie Pichard basket bag

In the wake of the passing of Hugh Hefner, what is your opinion of the image of the playboy bunny that he created?

Hugh Hefner made something crazy. He enjoyed sex, he enjoyed women, because women are the most beautiful things on the earth. I have a big collection of Playboy at my place – for me it is my favourite magazine.

Why were you interested in shoes in the first place as your medium of creativity?

I make shoes to tell stories. Before this, I was making clothes, but I felt a bit lost as it wasn’t very artisanal – I love artisanal creations more than fashion. I love the way you make something. One day, I discovered the last shoe factory of Paris, and I fell in love with what they were doing. I saw one of the workers working in an atmosphere of the smell of glue, of dust, making these tiny and delicate shoes, and I just thought this is so cool!

Amelie Pichard Rodéo Glitter Gold

Who or what else are your inspirations?

It is always women of the past, who aren’t in our world anymore – they are from a time long gone so I can’t meet these women, I don’t know these women: it gives me simply fantasy, and everything starts with fantasy. Sometimes I just need to see an image – you know the movie Paris, Texas ? For five years I fantasised about this movie, despite having never seen it, just pictures – after that I designed a whole collection around the images I knew. For me it is all about fantasy, and telling a story I want to tell that is always between the past and the present. Once I have finished designing, shaped by the past, I will imagine the shoes on my friends who are modern and contemporary: if the shoes appear right then I am happy.

What was the last thing that made you excited?

The launch of the shop – it was crazy because we made a fête au village, so all the street was totally full! We partnered with the bar opposite us and had a Claude Francois impersonator perform.

Tags: Feminism, interview, Twin interview, Twin magazine

08.10.2017 | Art , Culture , Fashion | BY: Jo Thompson

There are so many reasons why a sane person might avoid working with our other halves at all costs; mixing the ego of creativity with the power dynamics of a relationship seems like a recipe for disaster. And yet some of the most celebrated creative pairings in fashion and beyond have been couples. From Andreas and Vivienne to Inez and Vinoodh, there’s no shortage of partnerships emotionally evolved enough to sustain making beautiful things with the person they share a bed with. Shame on all of us for not making a go of it, perhaps?

Twin contributors Stevie Verroca and Mada Refujio are another enlightened example. Crediting themselves as Stevie Mada, the couple have been working together since meeting in California in 2010. They take photographs that are full of colour and buckets of the sun-drenched outdoors, tempered by the cooler airs of their current home in NYC. Their subjects are lovingly rendered and playfully directed, with winding poses that remind us that it’s actual human beings who wear the clothes in editorials. The body’s physicality is often at the forefront of their work, and the combined adoration of an evenly balanced female and male lens unlocks something pleasingly sensual for their viewer.

There is lots of beautiful work by Stevie Mada to be found out there – for the likes of V Magazine, Interview and Teen Vogue to name a few – but very little about them as people. Before their feature in the new issue of Twin hits shelves, we caught up with the pair to get to know them better.

What kind of work were you each making before you met?

Mada: Some light book keeping .. haha. I was playing around with some paints and mixed media before photography found me.

Stevie: He’s modest, he’s a painter. I’ve always taken photos.

You used to be based on the west coast. What prompted the move from LA to New York?

M: A more creative energy was drawing us to NYC.

S: We craved a change in culture and style. Very much miss the weather and ease of CA, but it’ll always be there. It felt like the right time for a change.

Did that move have an impact on your work?

M: Extremely.

S: Night and day.

We tend to think if the photographer as a single eye, how do you align your perspectives to create cohesive work?

S+M: Thanks for saying our work is cohesive 🙂

M: I think it’s like splitting a milk shake. You decide on the flavour before you decide to share.

S: We’re becoming firmer in our individual likes through experience and we happen to be fortunate that our shared likes outweigh the dislikes. Plus, whatever I say, goes. ha!

You seem to work a lot in exterior locations – do you prefer them to the studio?

M: I love to work outdoors – partially the reason I don’t paint anymore. Following the sun and the earth’s textures really makes me feel connected. Although a studio shoot does have its appeal from time to time.

S: Yes! Light, colour, space. I never get tired of it.

© Stevie Mada

That said, the environment of your images never overwhelms the subject – what draws you to that?

S: We like open spaces – probably because we grew up near deserts in the LA valleys.

Do you have any interest in making work without a human subject?

M: Yes, but working with cool peeps outweighs that. 🙂

S: I love looking at photographs of empty spaces. I can look at Stephen Shore for hours. But to take them myself, I crave people.

The ‘naughty & nice’ story you shot for the newest issue is very playful but also very sexual, how did you approach the shoot?

S: I’m naughty, Mada’s nice 🙂 It really is a female/male perspective on sexuality and femininity. Can you tell which is which?

There is a very rich, almost painterly quality to your images – how do you think about colour?

M: Colour is the 5th element.

S: It’s my obsession.

Do you ever hope to work on any individual projects, separate from each other?

M: I’m open to it, but no.

S: I have fun doing what I love the most with my best friend.

© Stevie Mada

How do you see your partnership developing in to the future?

M: Kids? (we’re a couple). I LOVE short films!

And to close on something lighter – do you have a favourite anecdote about working with the other?

S: Mada loves to wear a t-shirt with Rihanna’s baby photo printed on it. It’s become a uniform.

M: Stevie blushes when you compliment her.. haha, BiG time! Try it!

Tags: Stevie+Mada, twin, Twin interview

17.09.2017 | Blog , Fashion | BY: admin

The room was succulent with energy before the show had even started, but Molly Goddard SS18 trumped all feverish expectations as it began. Opening with Edie Campbell, an e-cigarette dangling from her lips, the show offered a strong, louche party girl spirit, wrapped up in signature smocks and empire lines.

Taffetas, sequins and dense cotton was finely rendered here, with Goddard honing in on fine details as much as the big, stand-out aesthetics which have made her show one of the must see of the season – hell, even Sadiq Khan was on the front row.

Finely tuned ruche detail lent organic curves to backs and sleeves, while juxtapositions of form gave fresh vibes to familiar silhouettes. Cropped cardigans and blazers in rich tangerines, lemon-curd yellows and midnight blues translated the Molly Goddard girl into a more contemporary setting, while sequin smocks and sheer dresses were the wearable, fun escapism we’ve all been looking for.

“The doctor told me to watch my drinking. Now I drink in front of the mirror.” the show notes quipped: the show itself an exuberant realisation of the confident, funny, playful and seductive Molly Goddard girl that we have come to love so well.

Molly Goddard SS18| © kamil kustosz

Molly Goddard SS18| © kamil kustosz

Molly Goddard SS18| © kamil kustosz

Molly Goddard SS18| © kamil kustosz

Molly Goddard SS18| © kamil kustosz

Molly Goddard SS18| © kamil kustosz

Molly Goddard SS18| © kamil kustosz

Tags: Molly Goddard, Molly Goddard SS18, Molly Goddard SS18 dress, Molly Goddard SS18 report, Molly Goddard Twin, Twin interview, Twin magazine

26.04.2017 | Art , Blog , Culture | BY: Laura Isabella

Twin first came in contact with Cara Mills at her Central Saint Martin’s degree show where she presented The Labour of Ideas — a giant shredder which methodically rated then shredded hundreds of her art ideas which fell like snowflakes, gradually amassing to a five foot mound of destroyed work plans. Mills took this art work and developed a second piece, Painting Machine a highly visceral work which spluttered and almost aggressively threw paint creating a new art work experience every day. Fresh off the back of her recent exhibition at Fuimano Projects, Machine: Part A, Part B, Part C & so on… Twin sat down with Mills on the sunny rooftop terrace of RCA where she is currently studying to talk about what makes an idea art and how it feels to be a female artist in today’s landscape.

I loved The Labour of Ideas so much. It draws on all these projects you had in your mind and you’re making all of them, in a way — was that the point?

Yes! I get bored really quickly with my ideas, and I thought there was something interesting about the process artists go through to make ideas and why they chose one and why not another and where do those ideas go when you don’t use them? Where do your thoughts go when they’re forgotten? They’re still there, but not being realised or spoken. I wanted to see their full potential. It was all about this concept that I wanted to make something physical but using all these ideas and I was tongue tied on how to approach that and do it. What was ironic about the piece was there was no hierarchy between the ideas – there was in the ratings sense that they were all rated out of ten – but at the end they all created this pile, and they all had the same shredded weight in this pile.

You had a lot of ideas, the pile was impressive!

It was five feet! I think I started writing down my ideas from March until the degree show, like ten hour days of writing down ideas. The sound of the shredder was really visceral. You became very aware that things were being shredded and destroyed, but that you were also creating.

So in a way all those ideas led to this final idea, The Labour of Ideas machine?

No, it was more a series of tests… I was really inspired by auto-destructive art, that something could be destructive but also creative. Looking at it now, that’s what I was doing. Also the systematic approach – one of the ideas in the shredder was ‘Make a piece about shredding your ideas’ so it was very much in the project. When I’d finished the piece I was empty of ideas… I didn’t really know where to start again. So, that was the end of the idea culmination — but I still write all my ideas down.

It’s really interesting to think about what makes us realise and not realise our ideas…

I sometimes wake up in the middle of the night with an idea for a painting, then don’t do it. What interests me is why? I’m interested in ten years time to look back on my ideas, and maybe then I’ll have one of those ideas I really want to make at that time!

I also liked how with The Labour of Ideas that you could see the ideas, and see the performative piece and machine and take from it what you wanted.

At the CSM show, the same people kept coming back. People were saying that they felt like over time they came back a few times and told me they felt like they were killing my work, like a piece of your work is dying by me coming back, because they’d be reading the idea then watching it shredded. It’s like if you caught it at that moment then you saw it, but then it was shredded, deleted. It’s like you’ve made an idea in your head, is that done? Or do you need to realise it? I was interested in the actual physicality of an idea, like it was one pile made up of hundreds of ideas, metres and metres of paper.

Do you have a mission statement or motive behind your need to create art?

I think it’s about communicating ideas really. I think you get an itch to get it out of you. If it’s stuck, it’s not enough to say it or draw it, you need to make it and leave it there and let it manifest. The journey between thinking and making is really hard.

Your most recent exhibition showed The Labour of Ideas and Painting Machine. What is it about making these really visceral present machines?

It’s about detachment of myself as an artist, and as a creator. I like making something and setting up a situation and letting it happen. The machines will be churning away. I’m very interested in the gallery time frame, the gallery day being the limit but also the potential of the work. The solo show I recently did was three and a half weeks long, so during opening hours that was when the machines were going. The pile would never get any higher than it would be allowed to than the days in the gallery. They’re part of the work. The machines performing and I leave them and the audience see that process.

There’s an artist called Michael Stailstorfer who installed an art piece ‘Forst’ at Sammlung Boros in Berlin. It was a steel machine frame which turned a tree trunk and leaves on the ground, as the machine circled gradually the leaves and branches turned to dust creating piles on the floor — first leaves, then dust. I went to see it a few times, and each visit it was a different experience in the two year life cycle of the art works presentation.

That’s so interesting — something I’m thinking about a lot at the moment is ‘what is destruction’? So I’m using a lot of sandpaper on sandpaper and do we expect something to be grounded to flour — when does destruction become creation? When is that? Who decides that? I think what was interesting about the show was that with the Painting Machine it was chucking paint at the wall and kind of being destructive but also creating moments, and with The Labour of Ideas you could come in on the first day and it was a tiny pile of shredded material, and you could come in on the last day and it was this impending five foot mound!

Both could be seen as live sculpture in a way, and also be interpreted on so many levels…

I don’t want to make highly cerebral work only accessible to artists and intellectuals, I want to make something visual that people can interpret in different ways. I’ve looked a lot at performance work and I’m really interested in that — how much the audience plays a role, and what expectations artists put on their audience to complete a work. With ‘Painting Machine’ it was a very different experience depending on whether was moving, or when it was off. I like with kinetic work when something is moving it’s very different when it stops, sort of like how people are very different when they’re speaking to when they’re not. When it was moving it was aggressive and painting and when it was off it was very sculptural and poetic.

I was wondering if we could talk a bit about your experience as a woman in the art world?

It’s funny that you say that… on Facebook this morning I saw a post which said “Enough of Jackson Pollock”. It looked at Lee Krasner who was Pollock’s wife, who was making incredible paintings, and it was so insane because as soon as Jackson Pollock died she went into his studio and her paintings got so much bigger… I find that every artist I’m reading about are all men. I find it really frustrating. I think female artists are making incredible work, and I think historically men were more written about but today I think it’s really important for female artists to be louder otherwise it’s just going to continue to be a man’s world.

How do you navigate that?

I think you just don’t tolerate it. You just see yourself as an artist whether male or female. I think female artists need to not be afraid about working in such a male industry. Just be aware of it, and don’t take any shit.

Tags: Art, Twin interview, Twin magazine, Twin XVI

Twitter

Twitter

Tumblr

Tumblr

YouTube

YouTube

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram