Last night Twin came together with Shinola to celebrate the work of photographer Don Hudson. This is what happened…

Shinola’s London store is located at 13 Newburgh Street Soho W1F 7RS.

05.06.2015 | Fashion | BY: Mariella Agapiou

Last night Twin came together with Shinola to celebrate the work of photographer Don Hudson. This is what happened…

Shinola’s London store is located at 13 Newburgh Street Soho W1F 7RS.

03.06.2015 | Art , Blog , Fashion | BY: Clementine De Pressigny

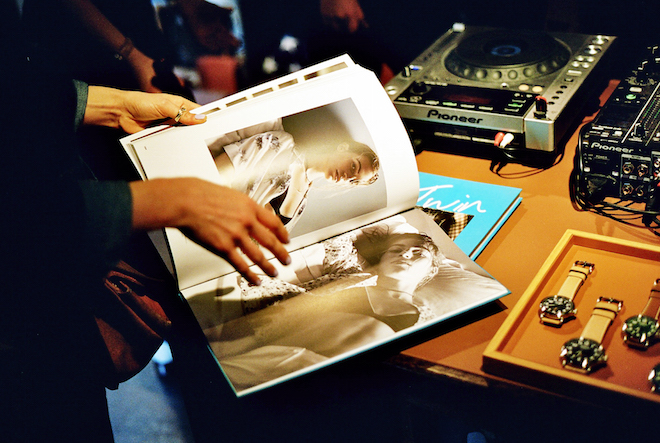

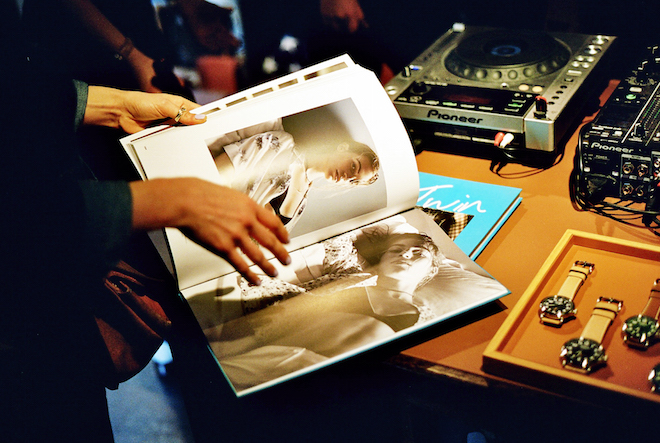

To celebrate the release of Twin issue 12 we have teamed up with American-made goods company Shinola to present the striking work of Detroit-born photographer Don Hudson, including previously unseen images. The 12th edition of Twin is all about attitude, and Hudson’s powerfully candid images are testament to the playful, tough and collective attitude of the long troubled Detroit and its surrounding areas.

Hudson’s photography naturally resonates with Shinola, a company that is deeply embedded in the city of Detroit. They are committed to returning some of Motor City’s former industry glory by choosing it as the location for producing their handmade watches and bicycles. Shinola has created local jobs and cultivated new expertise, building a strong sense of community and renewed pride in American craftsmanship.

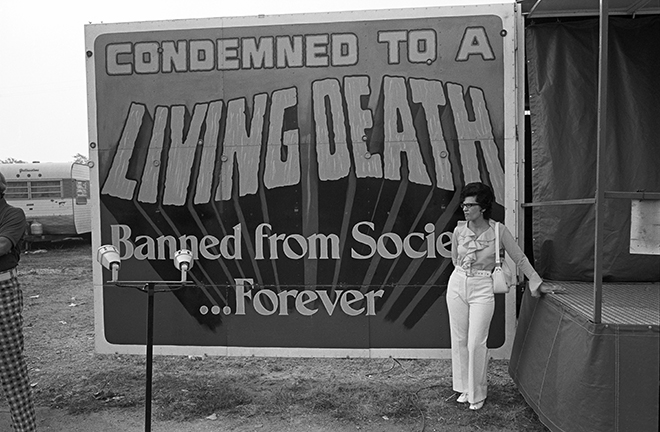

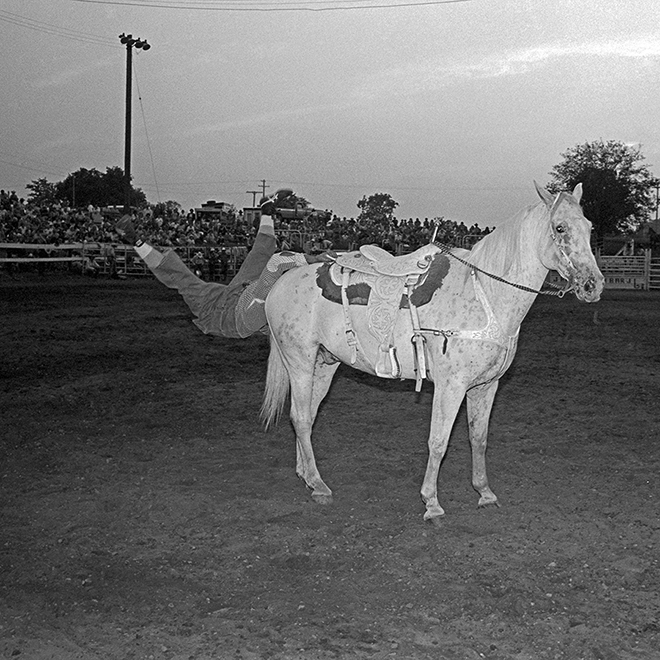

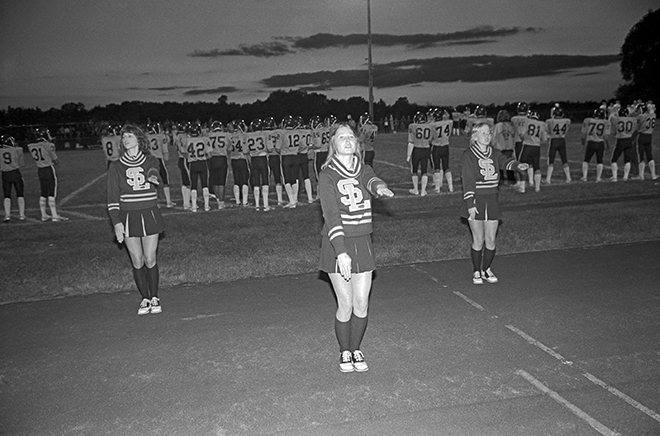

Following in the footsteps of the likes of Gary Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and Robert Frank, Hudson’s photographs, taken during the 1970s, are a time capsule of American life from his point of view. Shooting at local fairs, rodeos, carnivals and parades, Hudson captured moments of communities coming together for a fleeting but all too important moment of carefree fun.

Here Don Hudson tells of how his love for photography developed, why he describes himself as ‘proudly amateur’, and what he wants to capture when he looks through the lens.

I was born in Detroit but grew up nearby, in a little town called Plymouth on the edge of Wayne County. The seed for my interest in photography was planted when I was a kid, when I was the one being photographed. I grew up in the 1950s and when the camera came out we became subjects, we had a certain place to stand, to look. Thinking back, the idea of the camera as a transformative machine must have lodged itself in my subconscious back then. My interest in it really took off when I got to high school age. I had a couple of friends who ran the yearbook and had built darkrooms, so I jumped in with both feet. I built my first darkroom in my mother’s laundry room—it was kind of a set-up, known-down construction on top of her washer and dryer, with the windows all taped up. I was fascinated by the magic of the darkroom.

Then I graduated from high school and went on to university, but I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I spent three years doing a Liberal Arts degree and drifting more or less, then in 1972 I decided that the only thing I really liked to do was photography, so I applied to an art school in Detroit, CCS (College for Creative Studies)—it’s funny because I recently realised that Shinola actually have their watch factory on the campus. I really delved into the technique there, I learned the zone system, I became a lot better technically. I was also exposed to the history of photography and came into contact with more people who were into doing the same thing I was. During that period what solidified in me—getting back to the power of the camera—was having a huge amount of respect for how the camera sees things. I want to let the lens record as much information as it can. My whole thing—the only thing I was interested in—was what was coming straight out of the camera.

The photographs that are in my book, From the Archives, were taken during the Seventies, which is when I was coming of age photographically. Lee Frielander and Garry Winograd were coming out with their books at that time, and a few of my friends and I looked their work and thought that’s it. They were in the generation preceding us and what we wanted to do was in reaction to what they were doing. That approach which looks like documentary photography, it’s very straight, but it’s basically documenting your own relationship to your culture through photographs.

A lot of what I shot was public events. I searched out parades, carnivals, festivals, fairs, rodeos—places where there was a lot of social energy going on. I spent four years photographing high school football games. Every Friday night the community was all about the football game.

I describe myself as proudly amateur because I took photographs purely for the love of it, there was never a commercial aspect to my work and no ambition in that regard. I’m lousy with self-promotion; I’m just not a person who can do it. I’m going to do this regardless of whatever popularity may come of it.

I think of photographs like this: they look like the truth, I approach them with a high degree of respect for the way the camera sees things, but whatever I decide to put four edges around is always going to put the scene into a questionable context. They look like the truth, but what is the real meaning of the image? You don’t know what came before that moment, you don’t know what’s coming after that moment, all you’re seeing is one little facet of time and space. That’s what’s cool about photography too; it’s intimately involved with the sense of time. I think it was Winogrand who said photographs are like new facts. They’re new facts about life. Over time there’s a certain power that the photographic image gathers, and I’m enjoying that now, whatever small ripples these photographs may be making.