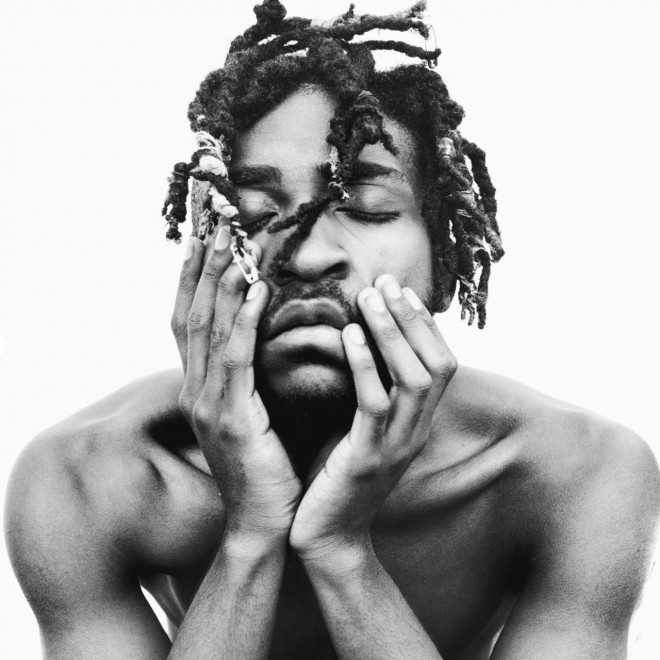

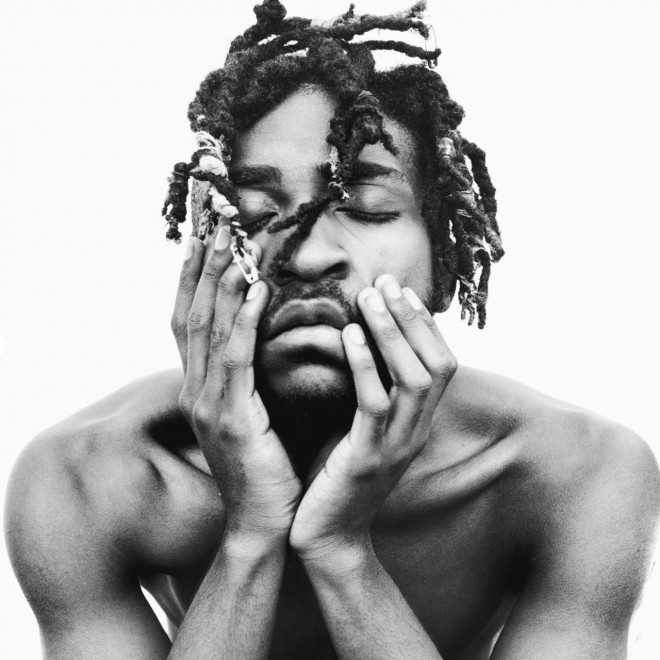

Born and raised in LA, photographer Sequoia Ziff has a magical way of merging fantasy and ultimate realness. Her photographs present human flaws in a complex light, holding in tension in a combination of vulnerability and spirit in striking, monochrome portraits. Ahead of her opening at Saatchi Gallery in London (where she is now based), Twin catches up with Sequoia to talk photography style and the magic of portraits.

How did you get started in photography and what’s your favourite camera to use?

I have known that I have wanted to be a photographer for as long as I can remember. It has always been my obsession. I worked on shoots through high school, decided not to go to college and have been living for it since. I am pretty low maintenance when it comes to gear, I found what works for me early on and have only made minor changes as my style has evolved. I have always worked with Canons, I started on film and now tend to work with the same camera for every shoot, a Canon 5d Mark 3.

Why black in white over colour?

Taste. A lot of the time, it’s just what I think looks better. It removes a sense of time and place and keeps the focus on connecting with the subject. I do love colour though….in moderation.

© Sequoia Ziff

Why portraiture?

I love people. Having your photo taken is a vulnerable process, and my job is to soul gaze all day long. That kind of vulnerability can be uncomfortable for people, and I enjoy helping people feel beautiful, just through the process of shooting them.

How did your style develop?

I have always been really specific in what I like aesthetically: old architecture, old movies, vintage clothes and a sense of timelessness. Anything that combines that with some haunted magical realism is always a bonus.

What is a good photograph to you?

One that makes you feel deep empathy and one that allows you to daydream.

© Sequoia Ziff

Tell us about the worldwide tribe project. How did it come about?

I was the featured artist at Summit at Sea this year, the idea was to humanise the refugee crisis and dismantle the fear by bringing larger than life size portraits to the centre of the ship. I had known about the amazing work that Worldwide Tribe does and contacted them about partnering and ended up working with one of their partners on the ground in Greece documenting portraits and life in the camp. Excited that the show is coming to London next month, and will be featured at the Saatchi from August 9-31st.

Has Instagram helped or hindered the medium of photography?

Both. I think that social media is an amazing tool for photographers, and it has meant that upcoming generations are more invested and interested in photography than ever before. It’s made everyone a photographer. It means that as an artist, you are able to build a network and self promote to a much larger audience, and from anywhere in the world.

© Sequoia Ziff

As a user of social media, I’m exposed to so many awesome artists that I may not have discovered without platforms like Instagram. That being said, I think that art often doesn’t have the intended impact that it would offscreen and in person. For me, social media is more of a business tool than an artistic one and the more time that I spend off-screen, the more present, inspired, and grounded I feel.

What are your plans for the rest of 2017?

Shooting as usual. Since moving from LA to London, I have been working a lot in the music industry, so will continue to be shooting a bunch of album artwork and press shots for bands.

Worldwide Tribe exhibition is at Saatchi Gallery London, August 9th – 31st 2017

Tags: Feminism, feminism photography, feminist photographer, interview, Twin XVI

Twin first came in contact with Cara Mills at her Central Saint Martin’s degree show where she presented The Labour of Ideas — a giant shredder which methodically rated then shredded hundreds of her art ideas which fell like snowflakes, gradually amassing to a five foot mound of destroyed work plans. Mills took this art work and developed a second piece, Painting Machine a highly visceral work which spluttered and almost aggressively threw paint creating a new art work experience every day. Fresh off the back of her recent exhibition at Fuimano Projects, Machine: Part A, Part B, Part C & so on… Twin sat down with Mills on the sunny rooftop terrace of RCA where she is currently studying to talk about what makes an idea art and how it feels to be a female artist in today’s landscape.

I loved The Labour of Ideas so much. It draws on all these projects you had in your mind and you’re making all of them, in a way — was that the point?

Yes! I get bored really quickly with my ideas, and I thought there was something interesting about the process artists go through to make ideas and why they chose one and why not another and where do those ideas go when you don’t use them? Where do your thoughts go when they’re forgotten? They’re still there, but not being realised or spoken. I wanted to see their full potential. It was all about this concept that I wanted to make something physical but using all these ideas and I was tongue tied on how to approach that and do it. What was ironic about the piece was there was no hierarchy between the ideas – there was in the ratings sense that they were all rated out of ten – but at the end they all created this pile, and they all had the same shredded weight in this pile.

You had a lot of ideas, the pile was impressive!

It was five feet! I think I started writing down my ideas from March until the degree show, like ten hour days of writing down ideas. The sound of the shredder was really visceral. You became very aware that things were being shredded and destroyed, but that you were also creating.

So in a way all those ideas led to this final idea, The Labour of Ideas machine?

No, it was more a series of tests… I was really inspired by auto-destructive art, that something could be destructive but also creative. Looking at it now, that’s what I was doing. Also the systematic approach – one of the ideas in the shredder was ‘Make a piece about shredding your ideas’ so it was very much in the project. When I’d finished the piece I was empty of ideas… I didn’t really know where to start again. So, that was the end of the idea culmination — but I still write all my ideas down.

It’s really interesting to think about what makes us realise and not realise our ideas…

I sometimes wake up in the middle of the night with an idea for a painting, then don’t do it. What interests me is why? I’m interested in ten years time to look back on my ideas, and maybe then I’ll have one of those ideas I really want to make at that time!

I also liked how with The Labour of Ideas that you could see the ideas, and see the performative piece and machine and take from it what you wanted.

At the CSM show, the same people kept coming back. People were saying that they felt like over time they came back a few times and told me they felt like they were killing my work, like a piece of your work is dying by me coming back, because they’d be reading the idea then watching it shredded. It’s like if you caught it at that moment then you saw it, but then it was shredded, deleted. It’s like you’ve made an idea in your head, is that done? Or do you need to realise it? I was interested in the actual physicality of an idea, like it was one pile made up of hundreds of ideas, metres and metres of paper.

Do you have a mission statement or motive behind your need to create art?

I think it’s about communicating ideas really. I think you get an itch to get it out of you. If it’s stuck, it’s not enough to say it or draw it, you need to make it and leave it there and let it manifest. The journey between thinking and making is really hard.

Your most recent exhibition showed The Labour of Ideas and Painting Machine. What is it about making these really visceral present machines?

It’s about detachment of myself as an artist, and as a creator. I like making something and setting up a situation and letting it happen. The machines will be churning away. I’m very interested in the gallery time frame, the gallery day being the limit but also the potential of the work. The solo show I recently did was three and a half weeks long, so during opening hours that was when the machines were going. The pile would never get any higher than it would be allowed to than the days in the gallery. They’re part of the work. The machines performing and I leave them and the audience see that process.

There’s an artist called Michael Stailstorfer who installed an art piece ‘Forst’ at Sammlung Boros in Berlin. It was a steel machine frame which turned a tree trunk and leaves on the ground, as the machine circled gradually the leaves and branches turned to dust creating piles on the floor — first leaves, then dust. I went to see it a few times, and each visit it was a different experience in the two year life cycle of the art works presentation.

That’s so interesting — something I’m thinking about a lot at the moment is ‘what is destruction’? So I’m using a lot of sandpaper on sandpaper and do we expect something to be grounded to flour — when does destruction become creation? When is that? Who decides that? I think what was interesting about the show was that with the Painting Machine it was chucking paint at the wall and kind of being destructive but also creating moments, and with The Labour of Ideas you could come in on the first day and it was a tiny pile of shredded material, and you could come in on the last day and it was this impending five foot mound!

Both could be seen as live sculpture in a way, and also be interpreted on so many levels…

I don’t want to make highly cerebral work only accessible to artists and intellectuals, I want to make something visual that people can interpret in different ways. I’ve looked a lot at performance work and I’m really interested in that — how much the audience plays a role, and what expectations artists put on their audience to complete a work. With ‘Painting Machine’ it was a very different experience depending on whether was moving, or when it was off. I like with kinetic work when something is moving it’s very different when it stops, sort of like how people are very different when they’re speaking to when they’re not. When it was moving it was aggressive and painting and when it was off it was very sculptural and poetic.

I was wondering if we could talk a bit about your experience as a woman in the art world?

It’s funny that you say that… on Facebook this morning I saw a post which said “Enough of Jackson Pollock”. It looked at Lee Krasner who was Pollock’s wife, who was making incredible paintings, and it was so insane because as soon as Jackson Pollock died she went into his studio and her paintings got so much bigger… I find that every artist I’m reading about are all men. I find it really frustrating. I think female artists are making incredible work, and I think historically men were more written about but today I think it’s really important for female artists to be louder otherwise it’s just going to continue to be a man’s world.

How do you navigate that?

I think you just don’t tolerate it. You just see yourself as an artist whether male or female. I think female artists need to not be afraid about working in such a male industry. Just be aware of it, and don’t take any shit.

Tags: Art, Twin interview, Twin magazine, Twin XVI

Twitter

Twitter

Tumblr

Tumblr

YouTube

YouTube

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram