The nature-culture dualism is central to the work of American artist, Mark Dion. Best known for his immersive sculptures and installations, his work examines how knowledge is gathered, interpreted, classified and presented. For his solo exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery, Dion examines our complicated – and conflicted relationship – with the natural world raising questions concerning the culture of nature and the environment. Twin spoke to Mark and The Whitechapel Gallery’s director, Iwona Blazwick to talk about the major exhibition, its curation and the ethical duties of artists and curators.

Thomas Rackowe-Cork (to director IWONA BLAZWICK): What initially drew you to Mark’s work?

IWONA BLAZWICK: I first encountered the work of Mark Dion in a gallery in New York in 1990. Marching across the white cube space was a line of wheelbarrows filled with exotic pot plants and cuddly animal toys. It was called ‘The Wheelbarrows of Progress’. It struck me that here was the legacy of minimalism but infused with narrative, politics and humour.

TRC to curator IWONA BLAZWICK: Can you tell me about the curation for this exhibition? Is there a particular circulation you had in mind for the viewer to experience the exhibition?

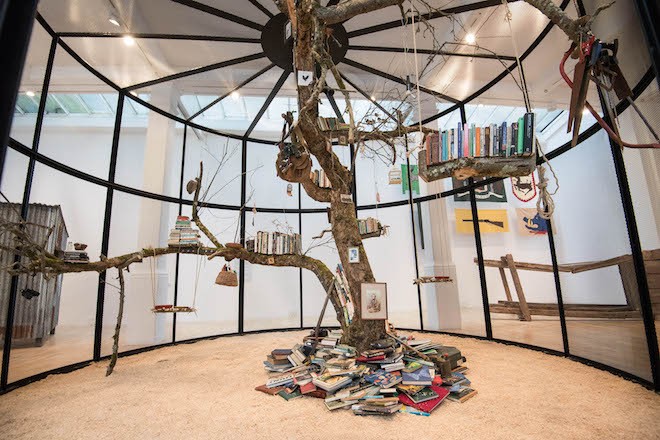

IWONA: Mark Dion is a scenographer and explorer. So, our curatorial approach was to take the viewer on a journey through a series of visual adventures. The voyage starts with life – 22 zebra finches in their beautiful Library for the Birds – proceeds through an expertly camouflaged yet hostile series of structures made for observation and hunting, through a studio for the contemplation of nature, an uncanny museum display and an archaeological dig; it ends with death in a room of ghosts glowing in the dark.

TRC to artist MARK DION: What drew you to the world of natural history and science as a mode of investigation?

MARK DION: I think one of the things that drew me to the world of natural history is that it is a field where we are asking exciting questions; who are we? Where do we fit into the world? What is the world? How did we get here? Conversely, I find the art museum asks questions of value and aesthetics – areas that were not especially inspiring to me. So, on the other hand, these institutions, such as museums of natural history and ethnography museums, tend to both ask questions and give answers. They turn the viewer into a passive viewer. Whereas the art museum has a very critical view – they don’t expect that you necessarily agree with the work of art. It is almost encouraged that you do not. So, I wanted to bring those two worlds together. But my principle motivation is a kind of love for nature and experiences and it is something that was always a big part of my life growing up and I can’t imagine it ever not being a part of my life. And with growing up in the city, you search for surrogates – you may not be able to get to the mountains every weekend or to the coast. But you can get to the natural history museum or the park.

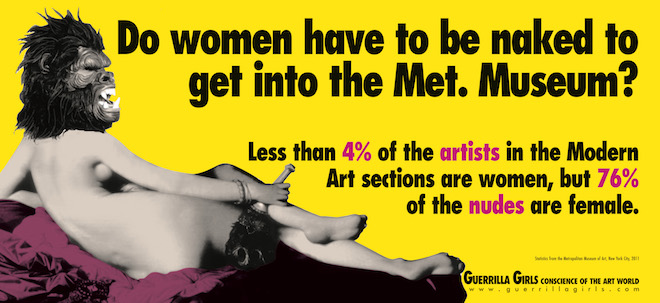

‘The Library for the Birds of London’ on show in Mark Dion: Theatre of the Natural World | © Jeff Spicer/PA Wire

TRC: The cabinet of curiosities is a theme that you repeatedly revisit in your practice – could you tell me a little bit more about why that is?

MARK DION: My interest was really in wildlife conservation and biodiversity. That brought me to the museum and then as I became closer to the museum, I became closer to its history for the collections. It was here that I discovered the tradition of the Wunderkabinet, which later peaked my interest in the 16th and 17th century collections. I found these collections really interesting because they contrasted so significantly from the imperial or colonial collections as they were not something of national prominence or filled with ideology. Rather, they are highly individual cosmologies. Though they are undoubtedly related to colonial processes, they are not the colonial museum in the same way. They are as much proto-scientific as they are spaces of magic, religion and superstition. So, that kind of mixture and hybridity, not only of the objects, but of their meaning as well, is important in thinking about how we move forward in terms of museum design – looking to the past and looking to the unexpected way things are put together.

TRC: The nature of a cabinets of curiosity seems to be concerned with collecting and classifying. Do you have a theme in mind when you collecting or making these material objects?

MARK DION: Very often, I go back to their original methodology where you would use an allegorical structure. I think that in trying to reconstruct those you have to also try to put yourself in the head of a maker from that time. So, you are intentionally putting things together that we may not put together today. So, let’s say, if you are using the elements of the seasons and you are putting them together based on the idea of fire, I try to ask myself; what does that necessarily mean? So, I find that really exciting.

TRC: So, you do not approach the curation of these cabinets thematically – could say then the curation is more intuitive?

MARK DION: Well I’m thinking about the themes that would exist in a historical setting and trying to mirror or refresh those. So, I am constantly thinking about their allegories. Very often, I look back at young Bruegel paintings, for instance, or something like that as a way of imagining what does the allegorical air look like?

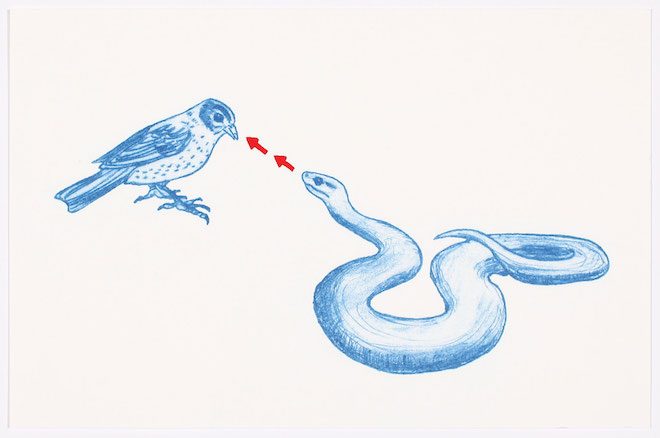

Mark Dion ‘World in a Box’, 2015 | image courtesy of Whitechapel Gallery

TRC to IWONA BLAZWICK: The cabinets of curiosities are already curated in a way – how do you go about curating the cabinets themselves?

IWONA: The artist makes his own cabinets of curiosity – our role is to immerse our visitors in them, encouraging them to act as detectives searching for the myriad clues embedded in Dion’s assemblages, drawings and wallpapers.

TRC to MARK DION: From the sort of themes that you are looking at; what are some of the most fascinating objects you’ve found over the years?

MARK DION: There are always found objects that you pull out of rivers and one of the most interesting things about creating pieces for this exhibition was that I was working with people that were not trained as archaeologists or artists. It was interesting to see how some of which had a very accentuated search image. Whilst others had a really difficult time just seeing. As for me, one of the most exciting things we found were those traditional objects that you embellish with cultural artefacts. For example, you may have a whale’s tooth and surround it with silver and engrave on it. The opposite of that might be a cultural object that is traced with worm tracings or oyster shells or slipper shells and things like that. Things that articulate that opposite. In many cases, I found it interesting that many of the young people working on these projects were entirely unable to tell the difference between a rock of flint and a cultural object. To them, it seemed unfathomable that a piece flint, for example, was not human made because the natural world just does not make something that strange. So, these things that articulate the natural affecting the artificial I see as bookending the cabinet of curiosities and accentuating the natural with the artificial.

TRC: Following on from that, do you think our relationship to a found object changes when placed behind glass?

MARK DION: Oh, absolutely. It changes over a period of time. For example, an artist like Robert Rauschenberg might find a glue into a collage a newspaper cutting from his day in 1953. Suddenly, today that is a very exotic newspaper, with a different time sensibility, and different make up. So, not only do they change by this process of becoming “museum-ified” but they also change dramatically just by getting a little bit older. Even with things here in the Thames Cabinet from the dig in 1999 here in the exhibition, someone was looking at them yesterday saying “Oh! SunnyDelight – does that still exist?”

TRC: Do you think that these found object lose some agency when they are placed in this context?

MARK DION: I do not think they loose agency. In fact, I think that they gain some agency, or the viewer gains some agency because they begin to see themselves in this context. What is important for me about the Tate Thames Dig (1999) is that people find themselves in it. It is not this notion that history happens to someone else, sometime ago. Rather, it is a continuity that is inclusive. We find ourselves in that, which also implies that this history goes beyond us. One of the most difficult things we face as a society, is this ability to imagine things going on beyond us. I feel that is why many seem not to care about leaving behind a mess.

Mark Dion exhibition | courtesy Kunstraum Dornbirn

TRC: Yes, it is incredibly hard to fathom the sort of everlasting element of material objects… the idea that things can live beyond us…

MARK DION: Absolutely. We are just a point in the continuum. And so that is sort of my real agenda with these pieces to emphasise this notion of a continuum. For that to happen, the viewer has to find something that they have touched, something that they know or are familiar with.

TRC: I sort of felt a sense of nostalgia whilst walking around the exhibition – would you say that this feeling or emotion plays a somewhat central role in your work?

MARK DION: I am always trying to guard against nostalgia. But at the same time, I think that I certainly have an affinity to materials that are well-made – that are crafted in leather and wood rather than in plastic. At the same time, I try to police myself against this golden ageing. It is the curse of nostalgia to imagine the past is somehow a purer, a better or a more superior time, which it clearly was not at least it was not for many of us. It would always feel artificial, for example, to place a laptop into a study of surrealism. I mean, that is not a good example, because the piece Bureau of the Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacy (2005) in this exhibition is a period piece that is meant to be a 1923 office.

TRC: Is there a hope to achieve anything by bringing these things back to the surface?

MARK DION: I want to cultivate the viewer who is more cautious and sophisticated. But at the same I want to be critical and to that you have to be affirmative. That is to say, to affirm people’s world views so you don’t feel entirely isolated – that you’re not the only one on the right road.

TRC: How do you think artists and have ethical duty or responsibility to bring certain issues to the surface?

MARK DION: I would not want to be prescriptive, but for me it is important. I mean, otherwise I wouldn’t really understand what the point of making are would be. I could understand why someone would want to make work as a self-expressive gesture, but I just do not understand why they would think an audience would only need to see that. I am interested in artists who are not afraid to have a didactic aspect to their work. Who are not afraid to say something and to have a position. That is the kind of art I like. So, I am not afraid to make that kind of art myself. At the same time, we have to face a lot of this stuff in society anyway, which is not particularly successful in terms of messaging. So, I wonder how to do that with complexity. I think for me, humour is part of the way to do that and also just trying to do things really well that builds a confidence in the viewer that is worth engaging with.

TRC: How do you think curators have ethical duty or responsibility to bring certain issues to the surface? Here for instance, the conservation of the environment.

IWONA BLAZWICK: The curatorial mission changes according to its institutional and social context. For us at the Whitechapel Gallery we are dedicated to offering a platform for contemporary artists – and they don’t have a duty to comment on issues. While World War II raged about him Morandi just continued to paint bottles. He is nonetheless a great artist. However, an artist like Mark Dion is exciting because he is able to respond to the environmental crisis in a way which combines ethics with aesthetics. He has spoken of his despair at our indifference to the fate of our planet – but I see this exhibition as being full of hope, making us reflect on our relations with other species while rekindling our sense of awe at the natural world.

Mark Dion ‘Theatre of the Natural World’ is on at the Whitechapel Gallery in London until 13th May 2018.

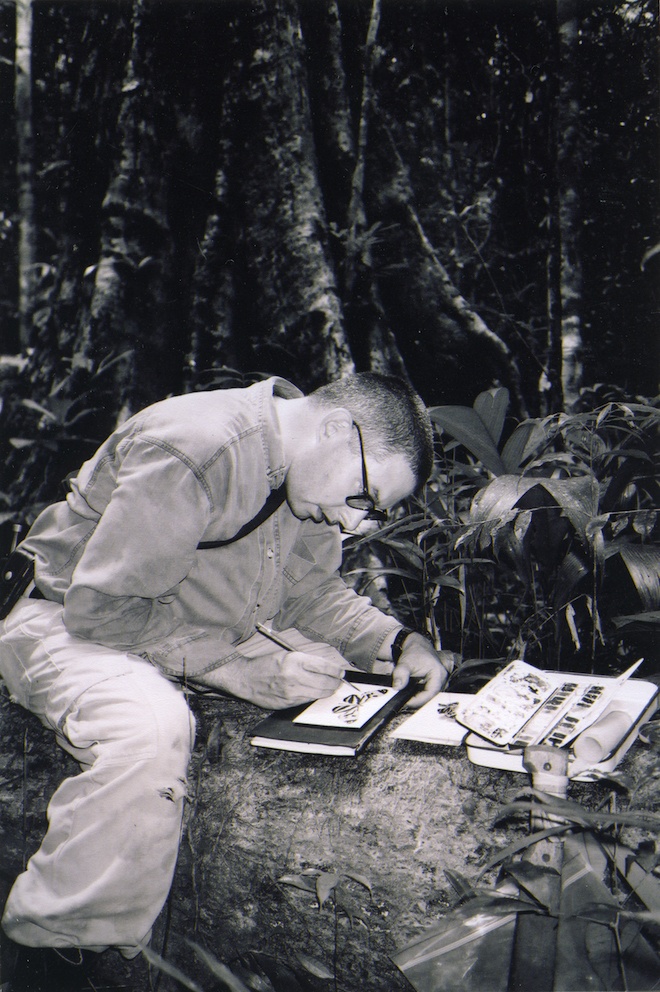

Featured image credit: Mark Dion in the rainforest of Guyana | Photo by Bob Braine, courtesy of Whitechapel Gallery

Twitter

Twitter

Tumblr

Tumblr

YouTube

YouTube

Facebook

Facebook

Instagram

Instagram